Legacy of Wonder

Posted on Tue., Dec. 22, 2020 by

The Huntington’s botanical gardens have long been shaped by the vision of Jim Folsom.

James P. Folsom, the Marge and Sherm Telleen/Marion and Earle Jorgensen Director of the Botanical Gardens, has transformed The Huntington during his 36 years at the institution. Photograph by Danielle Rudeen.

When young botany student Jim Folsom traveled from Austin, Texas, to The Huntington to interview for an assistant curator job in late August of 1984, he was completely turned off by the heavy traffic and acrid smog that hung over the Los Angeles basin. Having absolutely zero interest in living in Southern California, Folsom sleepwalked through his interview. Then he saw the gardens.

“I spent the entire time kicking myself for being so bland in the interview,” Folsom recalled. “Once I saw the gardens, I had no doubt I wanted the job.” Luckily, Folsom was offered the position to work under Director of Botanical Gardens Myron Kimnach and, a few years later, took over as director of the gardens and grounds—all 207 acres.

The Japanese Garden at The Huntington. Photograph by Martha Benedict.

It may be The Huntington that ended up being the lucky beneficiary. As he steps away from the institution after 36 years, Folsom leaves a spectacular legacy: a diverse collection of more than a dozen themed gardens, a rigorous program for botanical research and conservation, and a dedication to showcasing and teaching new generations and audiences about the endless wonders of botanical science.

“Jim’s ideas and vision have literally changed The Huntington's landscape,” said Huntington President Karen R. Lawrence. “When Henry Huntington was asked if he planned to write a memoir, he demurred and said the Library would tell the story. In Jim’s case, the gardens will tell the story.”

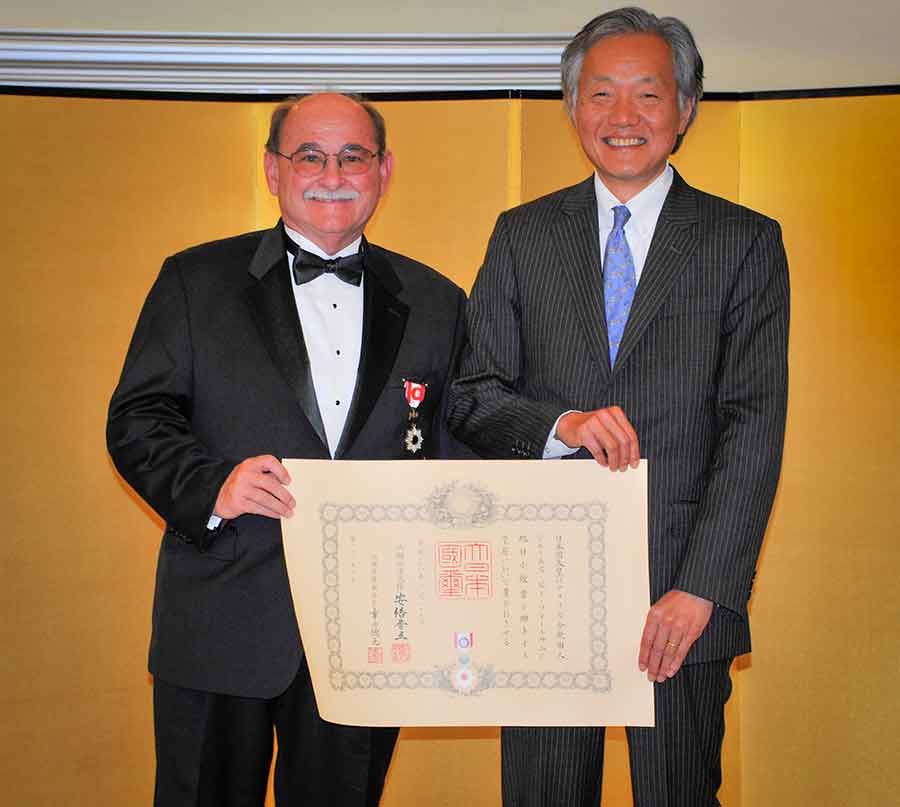

James Folsom poses with Consul General Harry H. Horinouchi on June 16, 2016, after being awarded the imperial Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette, for his work promoting Japanese culture in the United States. Photograph by Andrew Mitchell.

This deep appreciation for Folsom’s vision and achievements extends far beyond The Huntington community. In 2016, Folsom was awarded one of Japan’s prestigious meritorious service awards—the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette—for promoting Japanese culture through his work on the Japanese Garden. This year, Folsom was awarded the American Horticultural Society’s highest honor—the Liberty Hyde Bailey award—for lifetime contributions to horticulture that have included research, outreach, and leadership. “Under Jim Folsom’s guidance, The Huntington’s gardens have achieved an uncannily perfect union of scientifically significant research collections and astonishing artistry," said Panayoti Kelaidis, the Denver Botanic Garden's senior curator and director of outreach. “Jim has fostered a vibrant culture among his staff and made his garden the envy of our profession.”

With his classic humility, Folsom says credit should go not to him, but to the large and talented botanical staff he’s long treated as family, to his army of devoted volunteer docents, and to the many generous donors who have helped bring his plans to fruition. “I may be the pied piper,” said Folsom, “but it’s the people working with me and around me who made this all happen.”

***

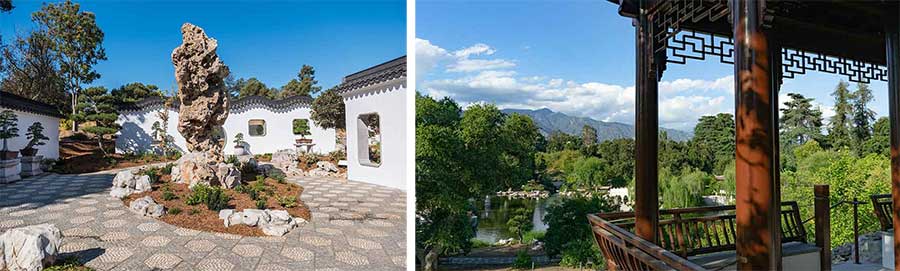

Left: Site of the Chinese Garden lake in 2002. Right: View of the Lake of Reflected Fragrance 映芳湖 in 2018, showing some of the original features of the Chinese Garden—the Garden of Flowing Fragrance 流芳園—that opened in 2008 (left to right): the Pavilion of the Three Friends 三友閣, the Jade Ribbon Bridge 玉帶橋, and the Hall of the Jade Camellia 玉茗堂. In the foreground is the Bridge of the Joy of Fish 魚樂橋. Photograph by Martha Benedict.

Folsom’s retirement coincides with the completion of what many see as his crowning achievement: The Huntington’s spectacular 15-acre Chinese Garden—Liu Fang Yuan 流芳園, the Garden of Flowing Fragrance—which started as what once seemed like an impossible dream of Folsom’s and has been more than three decades in the making under his leadership. But those who have worked with Folsom over the years say his impact on The Huntington is too large to be measured by any individual project or garden, stunning as that garden may be. His greatest legacy may in fact be the continued existence of the gardens themselves.

While it seems impossible now, Huntington Trustees were forced to consider closing or vastly downsizing the gardens during the fiscal strife of the late 1990s, said Steven S. Koblik, who became The Huntington’s president in 2001. It was Folsom in large part, Koblik said, who argued for the gardens, not only rescuing them, but working to shift them from behind the shadows of The Huntington’s library and art collections. “Jim’s real legacy is the centrality of the gardens,” Koblik said. “During Jim’s tenure, the place of the garden has been firmly fixed as a full equal of the other two collections.”

Two new features of the Chinese Garden in 2020. Left: The Cloudy Forest Court 雲林院, one of the architectural features within the Verdant Microcosm 翠玲瓏, the Chinese Garden’s new penjing complex. Photograph by Jamie Pham. Right: View from the Stargazing Tower 望星樓, situated on the highest point in the garden. The name pays homage to the nearby Mount Wilson Observatory—visible from the tower—and to the work of astronomer Edwin Hubble, whose papers are part of the The Huntington’s holdings in the history of science. Photograph by Aric Allen.

The broad support for Folsom has been so strong, Koblik said, because Folsom is so passionate and creative, and his projects have been so spectacularly successful.

“It’s impossible to say no to Jim. When he has a good idea, he’s having such a good time, people can’t resist helping him,” said Randy Shulman, The Huntington’s vice president for advancement and external relations. “When we started raising the funds for The Rose Hills Foundation Conservatory for Botanical Science, we didn’t even have a fully formed plan in place. People were giving because of Jim’s unbridled enthusiasm.”

The Rose Hills Foundation Conservatory of Botanical Science was inspired by a wooden lath house that once stood on Henry E. Huntington’s original estate. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

Magnetic and not easily dissuaded, “Jim has assembled a tremendous number of admirers that want to help with his projects,” said Sherm Telleen, a past chair of The Huntington’s Board of Governors who, with his wife Marge, has served as a Desert Garden docent for 35 years and helped endow Folsom’s position as director. “These were very fine gardens when Jim got here. Now they are exceptional.”

Whether it’s building a Children’s Garden rooted in both science and whimsy, or dismantling, restoring, and transporting a centuries-old magistrate's house from Japan to reassemble at The Huntington, or designing a conservatory building inspired by one that once stood on Huntington’s original estate, Folsom’s projects brim with historical authenticity, a deep love of plants, layers of thoughtful touches, and often, a little bit of magic.

“I’m big on soul, and I believe Jim has brought true and genuine soul to these gardens,” said Don R. Conlan, who has worked closely with Folsom while serving as a longtime member and the current chair of the Botanical Committee for the Board of Governors.

***

A young Jim Folsom took an early interest in nature—and getting his hands dirty in the soil. Unknown photographer.

James P. Folsom was born in 1950, in what he has described as the “drop-dead gorgeous” small east-Alabama town of Eufaula, where he was able to roam and observe, tend his family’s garden, and help grow bushels of summer vegetables the family would eat, can, and pickle.

Obsessed with plants from an early age, Folsom earned a bachelor’s degree in botany from Auburn University, a master’s degree in biology from Vanderbilt University, and a doctorate from the University of Texas at Austin, the place where he also met Debra, his wife and fellow botanist. Folsom expected to work at a small college, teaching and conducting botanical research and field work. Then someone put The Huntington’s job application on his door. “It was like they had written the job description based on my C.V.,” Folsom said.

In The Huntingon’s Ranch Garden in 2017, Kelly Fernandez (left), head gardener of the Herb and Shakespeare gardens, built a framework to support vegetables growing in straw bales, while Emma Ho’o—a plant science major from California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, at the time—spread mulch between the rows. The Trustees of The Huntington recently passed a resolution to rename the Ranch the James P. Folsom Experimental Ranch Garden. Photograph by Kate Lain.

Folsom has drawn from many of his life experiences in his shaping of the gardens. Coming from a family that nurtured a vegetable garden and preached the importance of self-sustainability, Folsom created both the Potager Garden, which seeks to replicate the bountiful kitchen garden the Huntington estate once relied on, and the Ranch Garden, which is full of experiments in urban agriculture. (The Trustees of The Huntington recently passed a resolution to rename the latter the James P. Folsom Experimental Ranch Garden.) Folsom served as a lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force, working in food services; today, his wood-fired pizzas and bread-baking classes for children are legendary.

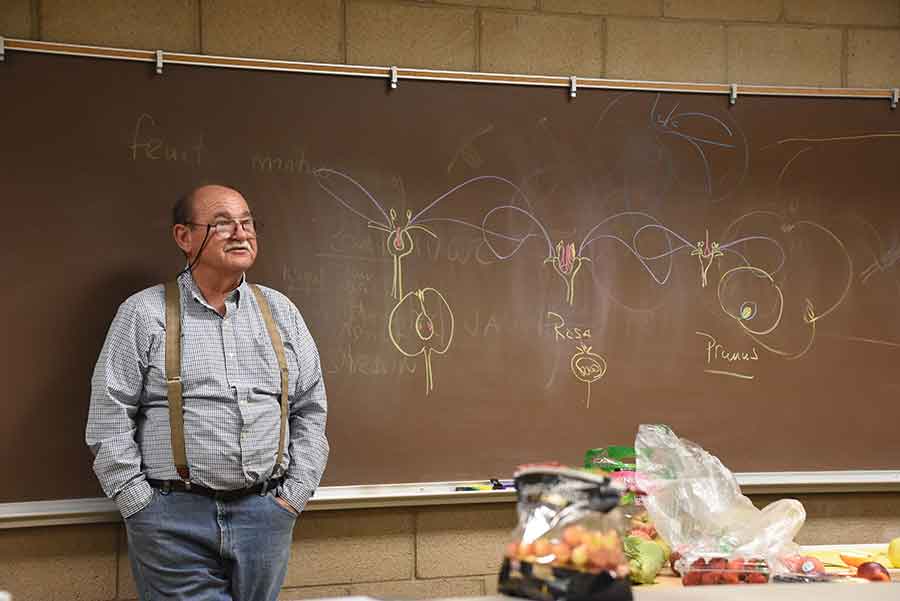

Despite his folksy demeanor, Folsom has a keen intellect. One of the things he’s proudest of creating are lecture series about gardens. “The Huntington has become the place for ideas associated with gardens and nature,” Folsom said. Folsom’s teaching is also legendary. Deeply committed to democratizing science and making it accessible and interesting to all, Folsom has presided over the dissection of a corpse flower live on Facebook, carved pumpkins with chainsaws in front of rapt audiences, and enthralled generations of schoolchildren as well as adults with hands-in-the-dirt lessons about plants.

In 2016, Jim Folsom provided outdoor and indoor instruction to this group of participants in a YWCA Girls Empowerment Summer Camp program. Photographs by Lisa Blackburn.

“His passion for plants is matched only by his desire to put them into cultural context,” said Phillip E. Bloom, the June and Simon K.C. Li Curator of the Chinese Garden and Director of the Center for East Asian Garden Studies at The Huntington. “For example, he combs Shakespeare to understand the literary significance of plants.”

“People, including myself, will follow Jim around the garden to hear him talk about a single plant,” said June Li, an art historian Folsom recruited to become the founding curator of the Chinese Garden. “He can make a weed exciting.”

Left: Lead project gardener Gary Roberson works in The Huntington’s new hillside cycad garden, a dramatic showcase for thousands of plants donated by the late Loran and Eva Whitelock. Photograph by Scott Berger. Right: Jim Folsom, in 2014, standing among several species of Dioon cycads in the garden of Loran Whitelock (1930–2014), author of The Cycads, the standard guide to the plants. Photograph by Kate Lain.

Folsom has also spent decades creating gardens that are not only beautiful but play important roles in plant conservation work. Many of The Huntington’s plant collections—including colorful succulents in the Desert Garden that rival any collection in the world, hundreds of rare cycads, and delicate orchids blooming among tropical foliage in the conservatory—have been carefully curated under Folsom’s stewardship to aid both conservation and botanical research. “Jim has created a plantsman’s garden with a focus on diversity, variety, and really special things, not just on beauty and design,” said Peter Raven, renowned American botanist, president emeritus of the Missouri Botanical Garden, and a close friend of Folsom’s. “These gardens are a window into the world of plants.”

Some of Folsom’s work to support conservation is less publicly visible. He has created an impressive research program, recruiting botanists trained at some of the world’s best institutions to join The Huntington to work on such topics as the evolution of cycads and the use of cryopreservation techniques to preserve plant diversity. Such work, says Conlan, “is more important with every step taken toward climate change. It shows you how far out there he thinks.”

In 2012, while working at the University of California, Riverside, plant pathologist Akif Eskalen discovered that the invasive polyphagous shot hole borer beetle was destroying trees in Long Beach, California. Wanting to know how many different species of trees in the area might be at risk, he approached Jim Folsom about conducting a survey of the 3,000 different kinds of trees on The Huntington’s grounds. Folsom let Eskalen and his graduate student set up a small research lab. Left: Akif Eskalen (left), now at the University of California, Davis, and Jim Folsom at a party for Eskalen at The Huntington. Right: Cake decorated with a depiction of a polyphagous shot hole borer beetle. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Folsom has also swung open the gates of The Huntington to scientists wanting to conduct research on the grounds. One of them is Akif Eskalen, a plant pathologist now at the University of California, Davis. In 2012, while working at UC Riverside, Eskalen discovered that the invasive polyphagous shot hole borer beetle was destroying trees in Long Beach. Wanting to know how many different species of trees in the area might be at risk, he approached Folsom about conducting a survey of the 3,000 different kinds of trees on The Huntington’s grounds. Folsom not only welcomed Eskalen and his graduate student but let them set up a small research lab.

“I can’t tell you how important that was for my research,” said Eskalen, who adds that the research paper he wrote based on work at The Huntington is his most cited work by far. “Jim opened doors,” Eskalen said. He still holds dear a memory of a farewell party Folsom held for him when he was moving north to Davis; the cake served at the party featured a perfect (and slightly glittery) image of a shot hole borer. “Top people are not always accessible, but Jim is,” Eskalen said.

***

Entering through a small blue door, children find themselves in an imaginative landscape at the Helen and Peter Bing Children’s Garden. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Asking Jim Folsom which is his favorite garden is almost like asking him which is his favorite child. But when pressed, he’ll volunteer an answer: The Helen and Peter Bing Children’s Garden.

With its exuberant rainbows, animal topiaries, sound sculptures, and misting volcanoes, the garden delights children (and adults) of all ages. For Folsom, it’s a been a labor of love. While the garden exudes spontaneity, it required—like almost everything Folsom does—years of careful planning.

“People don’t realize how much thought, planning, plotting, and failure goes into a garden,” he said. “You can’t just plant things because they look pretty.”

As topiary animals look on, children enjoy the shimmer and splash of toddler-sized fountains in the Helen and Peter Bing Children’s Garden. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

The Children’s Garden was an entirely new undertaking for The Huntington, where Folsom notes, “nothing had ever been designed for families.” He started by thinking deeply about how such a garden would fit into The Huntington ethos. “It couldn’t be that different. It couldn’t be a raucous space in the middle of a garden that’s contemplative and quiet,” Folsom said. “I wanted something that would seem like what Henry Huntington—who was a lot more whimsical than most people realize—would have built as a special place for his grandchildren.”

The garden was the result of years of work, study, and contemplation. For inspiration, Folsom, his wife, Debra, and their two children visited children’s gardens around the country, including a 4-H garden at Michigan State University, to gather ideas. He and Debra also spent a week at a National Science Foundation symposium on best practices for creating science centers for children. “At the end of that meeting, this was all crystallized,” he said.

A child explores a tunnel filled with prism-scattered light in the Helen and Peter Bing Children’s Garden. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Many of the features—the magnetic sand, a tunnel filled with prism-scattered light, and a sculpture that creates sound using pebbles—were a collaboration between Folsom and Ned Kahn, an artist-in-residence at San Francisco’s Exploratorium and MacArthur “genius award” recipient who remains a close friend. Some features, like the small blue door children walk through to enter the garden, were inspired by Disneyland. Some of the tiny footprints set in concrete leading to the door belong to Folsom’s son, Jimmy.

The Children’s Garden, which Folsom calls “a science garden,” is so dear to Folsom’s heart because it is a physical manifestation of how he believes children learn best. “The goal of the garden is not to teach but provoke. You notice there is no signage, no interpretation,” Folsom said. “The goal is to create wonder, to create wondrous experiments that are the beginning of learning.”

The attraction of magnetic sand is irresistible in the Helen and Peter Bing Children’s Garden. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

As someone whose career was sparked by the wonder of plants, Folsom says he is “sad across the board about botanical education.” Folsom is now working on a series of educational videos for children. “There are lovely lessons to be learned, and they are not fancy lessons,” Folsom said. “You don’t have to pull RNA out of chromosomes to understand the world around you.”

Folsom doesn’t teach about botanical science as much as entice. “We grow plants that are so exciting and interesting people are going to want to talk about them,” Folsom said. “You can teach botany using lettuce—it does all the right plant things—or you can use a plant like the corpse flower.”

Children explore the world of plants through hands-on science activities in The Rose Hills Foundation Conservatory of Botanical Science. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

Many of Folsom’s lessons, or wonderments as he might say, are sprinkled throughout The Huntington’s gardens without any fanfare. There’s the small pavilion outside the Children’s Garden hung with so many birdfeeders, it can attract dozens of hummingbirds at a time. In the faux bois trellises of the Rose Garden, there’s a carved owl and a tiny door, just big enough for fairies. There are also gardens within gardens, like the tiny underwater garden on the Conservatory’s lower level, filled with unusual plants and angel fish. “You won’t see that in any other garden in North America,” Folsom said. “We just have stuff nobody else has and we care about things nobody else does.”

***

Folsom is known for nurturing not only plants but people. He has a knack for recruiting just the right person for a job; many of his staff have been at The Huntington for decades. “He’s very supportive,” Li said. “He has this great curiosity about everything, and he really listens.”

Orchid collection specialist Brandon Tam pollinates a Paphiopedilum delrosi in a Huntington greenhouse. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

Brandon Tam, The Huntington’s orchid collection specialist, has worked for Folsom for 11 years. Tam first began working at The Huntington as a teenage volunteer. He was helping an employee install holiday lights in the botanical center and talking about his fascination with orchids. The employee gave Tam his business card and told him to give him a call if he wanted to try an internship working with orchids. The name on the card was Jim Folsom. The fact that Folsom was doing something as basic as stringing up lights is not surprising, said Tam. “Jim is a hands-on person,” Tam said. “He’ll never delegate a task he wouldn’t do himself.”

Tam not only got a full-time job working on orchids but also found a botanical soul mate: Jim Folsom had written his dissertation on orchids and remained deeply attached to the plants. When Folsom learned Arabella Huntington was a big fan of orchids, he too saw it as a natural area of emphasis and growth.

Two of The Huntington’s award-winning orchids. Left: This Paphiopedilum micranthum ‘Huntington’s Perfection’ FCC/AOS received the Merritt W. Huntington Award for “Most Outstanding Orchid” in 2015. Right: Lycaste consobrina ‘Huntington’s Finest’ AM/AOS CCE/AOS received the Butterworth Award and the Benjamin C. Berliner award. Photographs by Arthur Pinkers.

There were 2,000 orchids when Tam arrived; now the collection’s 10,000 plants comprise one of the largest and most diverse orchid collections in the U.S. The collection is focused on conservation and includes programs to breed, propagate, and share orchids. “One of the greatest lessons I learned from Jim was to make connections and collaborations,” said Tam. “There’s no way we can save all these plants by ourselves.”

Under Folsom’s lead, Huntington botanical collaborations now span the world. Tam has traveled to Ecuador to see how orchids grow in their natural environment. Researcher Raquel Folgado works closely with a lab in Australia to develop cryopreservation techniques that might save avocado cultivars, while botanist Brian Dorsey works closely with researchers in Mexico to understand the dispersal and evolution of cycads. Kelly Fernandez, head gardener for the Herb and Shakespeare gardens, has traveled to Oaxaca on behalf of The Huntington to learn about textiles, work she shares through The Huntington’s popular Fiber Arts Day. “Jim has shaped my career in botanical sciences by providing me with opportunities I could not have imagined,” she said.

Jim Folsom has created an impressive research program, recruiting botanists to work on such topics as the evolution of cycads and the use of cryopreservation techniques to preserve plant diversity. Left: Brian Dorsey, research botanist, kneels before a Dioon merolae that came to The Huntington from the collection of Loran Whitelock. Photograph by Kate Lain. Right: Huntington Cryopreservation Research Botanist Raquel Folgado supervises as Lourdes Delgado and Felipe de Jesús Romo Paz—graduate students from Guadalajara, Mexico—prepare plant tissue for cryopreservation. Photograph by Deborah Miller.

***

Folsom retires from The Huntington at the end of 2020. Eschewing pomp and ceremony, he has asked that anything done on his behalf go toward an endowment to maintain and purchase equipment needed by his garden staff.

As he ends his tenure at The Huntington, Folsom remains mostly lighthearted. At a recent virtual talk about the Chinese Garden, which cost nearly $55 million to complete, Folsom called his hiring “the most expensive mistake The Huntington has ever made.” In more serious moments, he says his long tenure, in a world where people change jobs frequently, is what has enabled most of his achievements. “If you’re constantly changing leadership, you’re constantly changing directions and what you want to do,” Folsom said. “Maybe that’s good for an institution, but it’s not good for a garden.”

Jim Folsom teaching a Botanical Artists Guild of Southern California workshop in 2019. Photograph by Gayle Uyehara.

“Because I’ve stayed here, it means the ideas I’ve developed—with teams of people—have had time to mature,” he said. “The development of the Chinese Garden was a 30-year process.”

Folsom is fond of saying that no garden is ever finished. “A tree grows, a branch dies, you get a new idea. It will never be finished,” he said. The same might be said of Folsom’s career. There are more blog posts to write, more lectures to give, and, of course, always more plants to discover.

Usha Lee McFarling is senior writer and editor in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington.