Hidden Within “The Three Witches”

Posted on Tue., Dec. 22, 2020 by

Henry Fuseli, The Three Witches, ca. 1785, oil on canvas, 24 ¾ x 30 ¼ in. (62.9 x 76.8 cm). Purchased with funds from The George R. and Patricia Geary Johnson British Art Acquisition Fund. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

When The Huntington acquired Henry Fuseli's The Three Witches (ca. 1785) in 2014, I could immediately see clues that there was something to discover beneath its surface. The paint texture gave me the first indication that the painting may have been made on a reused canvas and possibly painted on both sides. (Information about these initial thoughts and observations can be found in my 2014 Verso post, "More Than Meets the Eye.")

I knew that the next step toward proving my hypothesis about the reused canvas would involve X-ray analysis. With X-rays, you can see through layers of a painting and all the way through the support on the back. This allows conservators to understand the anatomy of a painting and sometimes spot hidden damage or changes that an artist has made.

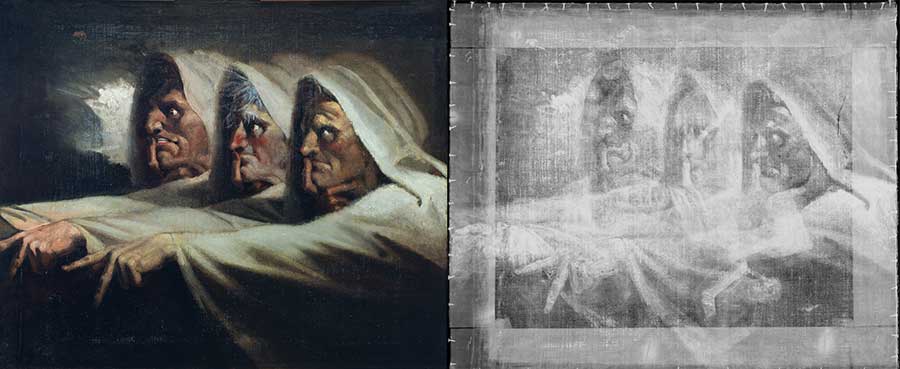

Henry Fuseli’s The Three Witches (left) and a digital X-ray of the painting. Digital X-rays provide a view through all the layers of a painting, revealing past damage or changes that an artist has made. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

X-rays are especially useful for a painting like The Three Witches, which has been lined or glued to a second overall canvas, preventing a view of the back of the original canvas. Recent X-rays of The Three Witches revealed even more than I had anticipated: proof that the canvas had been reused not once, but twice!

The same broad and bold brushwork you see on the surface of the painting can be observed in the X-ray. These bold brushstrokes indicate that Fuseli applied his paint rapidly. The freshness of his strokes, coupled with the dramatic contrast of light and dark, suggest that he painted this version of the composition from live models. Fuseli later painted two other versions of The Three Witches that are more stylized, one currently at the Kunsthaus Zurich in Switzerland and the other at the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon, England. Observations of the painted surface and the X-ray support the notion that The Huntington's painting is an earlier version of this repeated subject in Fuseli's oeuvre.

In addition, the X-ray reveals how Fuseli adjusted some details of the composition when he added a strip of canvas to the left edge, increasing the canvas size. With the expansion of the canvas, Fuseli adjusted the placement of the witches’ hands because the addition provided more space for their outstretched arms.

By rotating the X-ray 90 degrees clockwise, you can see a three-quarter portrait of a man. His face and collar are circled here in red. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

First you look, and then you look some more. The real discovery comes when you rotate the canvas in different directions. By turning the painting 90 degrees clockwise, you can see a three-quarter portrait of a man. We don't know who this man was, but you can see his face (as he gazes slightly to the right), his neckcloth or collar, and what looks like the outline of his left shoulder. It is possible that Fuseli had completed the likeness of this mysterious sitter because it looks like he added the highlights in the eyes. This is usually a final detail and indicates that the portrait was complete before Fuseli decided to paint over it and reuse the canvas.

Evidence of a second hidden painting can be seen by rotating The Three Witches 90 degrees counterclockwise. In this orientation, a smaller figure of a man with his arms raised can be seen on the upper right. This figure would likely have been part of a larger composition, but Fuseli did not do much work on it before reusing the canvas for The Three Witches.

By rotating the X-ray 90 degrees counterclockwise, you can see a figure of a man with his arms raised. The figure, circled here in red, would likely have been part of a larger composition that Fuseli left incomplete before he decided to reuse the canvas.

Studying what lies beneath the surface of a painting often leads to more questions than answers. Can we find enough evidence in Fuseli’s other works of art or writings to identify the unknown man in the three-quarter portrait? Are there drawings or other completed paintings that give us more information about the smaller figure and what narrative he may have been a part of? Are there other high-tech tools we can employ that can tell us whether these hidden compositions are directly under The Three Witches or on the back of the canvas?

The Three Witches themselves seem to be beckoning us toward these new avenues of research.

For the exhibition “Made in L.A. 2020: a version,” artist Jill Mulleady takes Henry Fuseli’s painting The Three Witches as subject matter and reproduces it, adding the flash glare of a photograph. You can see an installation shot of Mulleady’s reproduction here.

Christina O'Connell is the Mary Ann and John Sturgeon Senior Paintings Conservator at The Huntington.