A Founder and a Year

Posted on Tue., Oct. 15, 2019 by and

Henry and Arabella Huntington looked to the future by safeguarding the past

G. Haven Bishop, Interior of Huntington Library Building during Construction, 1919–20, gelatin silver print, 10 x 8 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Huntington’s Centennial Celebration kicked off with “Nineteen Nineteen”—a major exhibition on view in the MaryLou and George Boone Gallery through Jan. 20, 2020—which examines the institution and its founding through the prism of a single, tumultuous year, with a display of more than 250 objects drawn from The Huntington’s library, art, and botanical collections. What follows is the curators’ introduction to the book that accompanies the exhibition.

Alfonso C. Gomez, Henry E. Huntington’s longtime valet, sat for an interview in 1959, more than three decades after his employer’s death. At 66 years old, the Spanish-born “Gomez,” as the Huntingtons called him, held a storehouse of personal and institutional memories. He had spent more time with Mr. Huntington in his final decade than anyone else, and formalities between the two had eased.

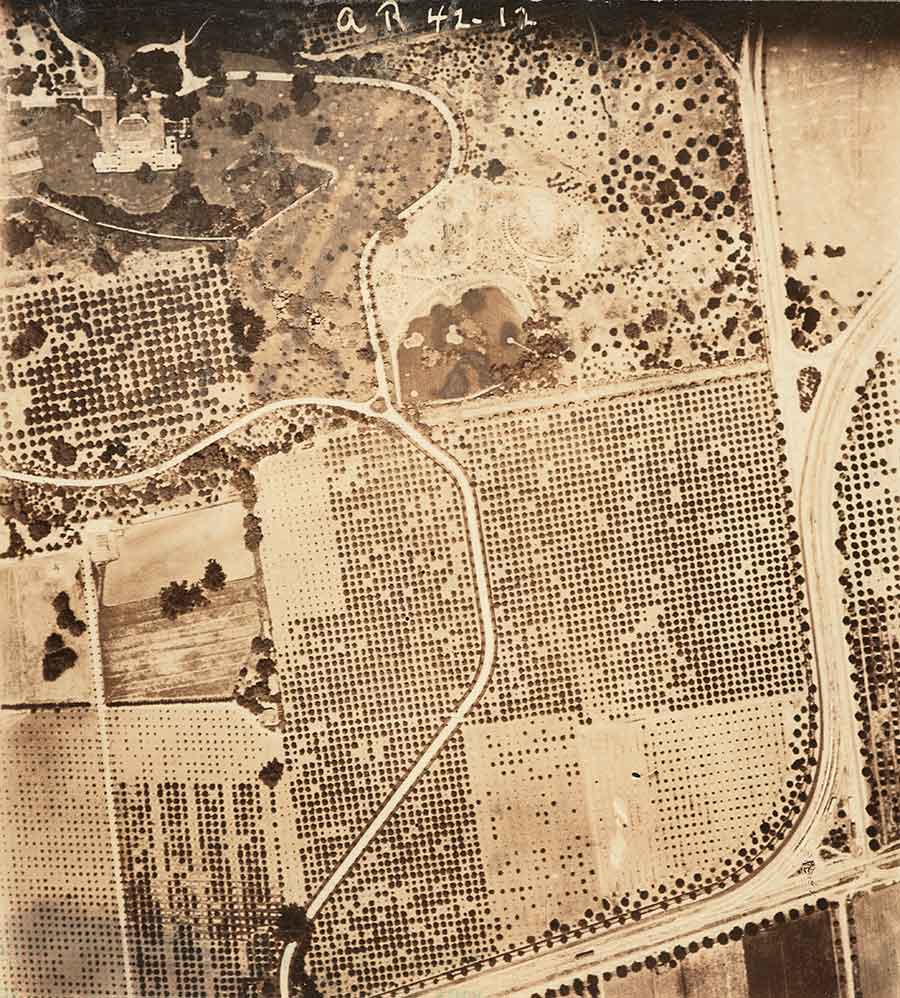

Gomez told a nostalgic story about an afternoon’s meandering walk with Henry and Arabella through their San Marino ranch. The couple strolled north from their mansion while Gomez kept an eye on Buster, Mrs. Huntington’s ill-mannered dog. After some distance, Arabella, nearly blind and walking with difficulty, stopped and spoke to her spouse. “You know, we are doing so much,” Arabella said. “I hope you will live many years yet, and I hope to live many years yet, but we are talking so much about it. We have got to make a decision where we want to be buried.” She put her foot on a spot, among the highest points of their property, and asked Gomez to mark it. Henry Huntington said little. Their final resting place had been decided then and there, by an infirm, elderly woman’s footprint on a Southern California knoll.

George H. Kahn, Henry E. Huntington with a Grandchild, ca. August 1916, gelatin silver print, 7 ½ x 5 ½ in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

That fateful walk took place in 1919. A world-shattering war, one that novelist John Dos Passos later described as a “blast that blew out all the Diogenes lanterns,” had just ended. As millions of soldiers and volunteers returned home, war’s aftershocks reverberated on other fronts: labor riots, racial-terror lynchings, and protest marches roiled the streets and countryside. At the Paris Peace Conference, President Woodrow Wilson and Allied heads of state carved up empires in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, adopting a punitive stance toward Germany in hopes of mapping a postwar world of enduring peace. On the other side of the globe in California, one of America’s wealthiest couples faced their own mortality and looked to the future by safeguarding the past.

Having made one decision about eternity, Arabella and Henry Huntington made a second one official. On Aug. 30, 1919, they signed a legal document bequeathing the gardens, books, and art collections to the public, “to advance learning in the arts and sciences.” The trust formalized an arrangement Henry had been cannily plotting for years. The establishment of the Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, on the grounds the founders had chosen for their eternal rest, would prove to be a monumental, even death-defying, act.

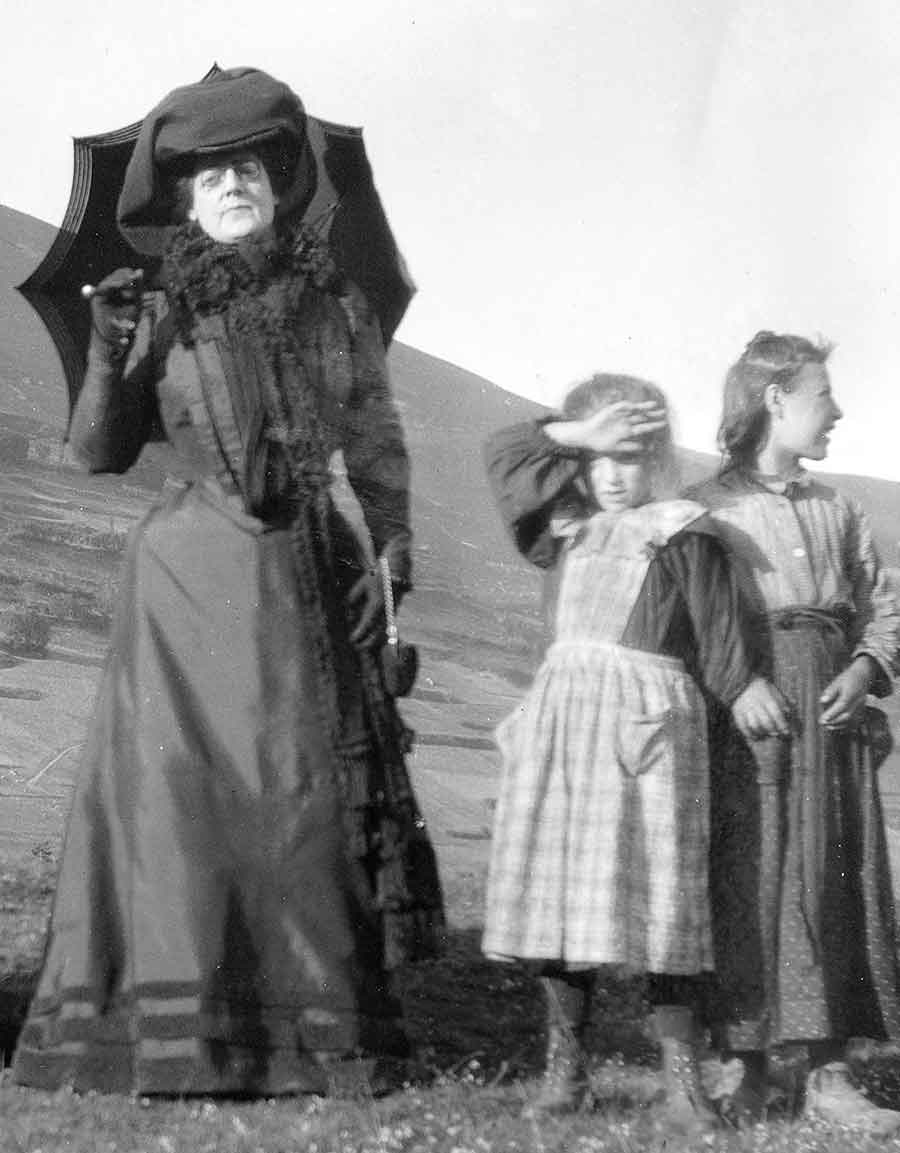

Arabella Huntington Traveling in Europe, ca. 1898. Arabella Huntington is dressed in black. Courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America, New York.

Once the plan was announced, reporters and others began to inquire about an autobiography describing his career. Huntington demurred. “This Library will tell the story,” he replied. “It represents the reward of all the work that I have ever done and the realization of much happiness.”

When considering a centennial exhibition, we decided to take Henry Huntington at his word. Rather than offer a narrow account of the collector and philanthropist, we chose to look outward to the nation and the world. Would it be possible, we wondered, to narrate 1919 by mining the millions of documents, objects, paintings, ephemera, photographs, and volumes found in The Huntington’s archives, galleries, and book stacks? We examined the institution’s founding and founders through the lens of a single cataclysmic year.

Nineteen Nineteen, the exhibition and this accompanying book, draws exclusively from The Huntington’s collections. The year and the actions of the institution’s founders are organized according to five themes—Fight, Return, Map, Move, and Build—verbs the Huntingtons lived and embraced. An additional section, Portraits, highlights personalities and lesser-known aspects of institutional history and memory.

U.S. Army Signal Corps, Aerial Photograph of the Huntington Ranch (detail), ca. 1919, gelatin silver print, 6 x 5 ¼ in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Henry Huntington traveled by private train to Philadelphia to undergo surgery in 1927. Gomez was by his side. It had been eight years since he and Arabella had signed the founding trust indenture, and three long years since her death. Huntington wanted the operation over and done. He longed to get back to California quickly. He was eager to build a cozy cottage, a tucked-away place where he could observe people enjoying the mansion, the library exhibits, and the gardens and grounds. “He said it so many times,” Gomez remembered. The giver was eager to see the response to his gift.

Huntington returned to San Marino in that same railroad car, the shades drawn in mourning to mark his death. He was eventually laid to rest next to his beloved Belle at the agreed-upon spot. A century later, his hope that their creation—an Edenic botanical garden and a superb collection of books and art—would outlive and honor them has exceeded his dreams.

James Glisson is Bradford and Christine Mishler Associate Curator of American Art.

Jennifer A. Watts is curator of photography and visual culture.