The Way We Were

Posted on Tue., Nov. 15, 2016 by

For Ernest Marquez, a lifelong obsession ends up documenting the evolution of L.A.

Passengers riding the Thompson Switchback Gravity Railroad from the Arcadia Hotel into Santa Monica, ca. 1887. Photograph by E. G. Morrison.

Even as a novice collector, Ernest Marquez found that he had a discerning eye for early images of Southern California.

“I’d go into an antique store and walk over to the corner that had a basket of photos, and I would find these things,” says Marquez, white-haired and mustachioed at 92. “Pictures of early Santa Monica or Los Angeles have the ability to call me.”

Boxers fighting in a ring in front of the Santa Monica Athletic Club, ca. 1934. The La Monica Ballroom is prominent on the Santa Monica Pleasure Pier in the distance. Photograph by Powell Press Service.

Throughout half a century of scouring flea markets, rare-book shops, and postcard shows, Marquez has been a man on a mission: to understand his forebears’ rich history as Mexican land grantees in what is now Santa Monica Canyon and its environs.

Over the decades, this History Whisperer’s dogged sleuthing has turned him into an authority on the 6,656-acre Rancho Boca de Santa Monica, where his ancestors built adobes, grazed cattle, and buried their dead.

Race car driver “Wild” Bob Burman at a Los Angeles racetrack, 1916; photograph by Stagg Photo Service.

But the process also resulted in an unintended bonus: along the way, he amassed a stunning collection of images from the 1860s through the 1960s that depict the region well beyond the bounds of the family rancho, land that relatives relinquished over time to cover taxes or sold for pennies on the acre to real estate speculators. Taken together, the photos and negatives illustrate the fast pace of development and growth that turned wide-open spaces into a densely packed metropolis.

Human card game at Gables Beach Club, Santa Monica, late 1920s; photograph by Powell Press Service.

Two years ago, The Huntington acquired Marquez’s collection, thinking it an impressive compilation of thousands of pictures that spoke to one man’s love for the region that had formed him.

Jennifer A. Watts, The Huntington’s curator of photography, described the photographic assemblage at the time as “the best and most comprehensive collection of its kind in private hands.”

Glass plate negative, made ca. 1905–10, showing what is now the California Incline road leading down to the beach and railroad tracks in Santa Monica. The Southern Pacific Railroad ran steam engines along these tracks between Los Angeles and the Long Wharf, seen in the distance at left. Unidentified photographer.

In the months that followed, Huntington staff worked to catalogue the collection and the final tally is now in: the trove is much richer and vaster than originally thought. It includes 10,936 photos and negatives (on film and glass), publications, research files, and other items, such as tourism brochures and event programs. The treasures fill 97 boxes.

About 3,000 of the photographs and negatives have been converted into digital form and are available online in the Huntington Digital Library and in the detailed collection index posted at the Online Archive of California.

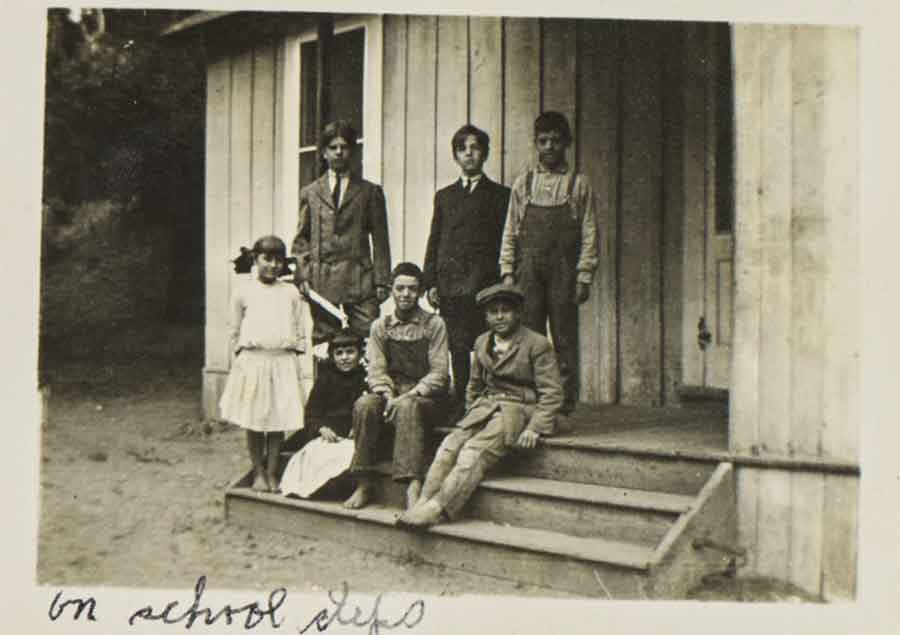

Children on steps of Garapatos School, Topanga Canyon, June 6, 1913; photograph by Theresa Sletton.

Among these are images of comely young ladies costumed as playing cards at a Santa Monica beach club (late 1920s), racecars roaring around the track at Legion Ascot Speedway (1916), Topanga Canyon residents (1913), and Southern Pacific railcars (1895) puffing along Santa Monica’s Long Wharf, demolished long ago but once envisioned as a potential port for Los Angeles. “What is truly overwhelming about the collection is that it was gathered based on one man’s passion for the history of place—‘his’ place,” says Paddy Calistro of Angel City Press, who has published three of Marquez’s books about local history.

Young women with ice cream cones on a Pacific Electric streetcar, Santa Monica, 1913; unidentified photographer.

Marquez, born in 1924, grew up in Santa Monica Canyon. After attending Canyon School and Santa Monica High School, he served in the Navy during World War II. He worked for a time in New York as a freelance magazine cartoonist and then returned to Los Angeles, where he supported his wife, Lois, and their three children as a commercial artist for aerospace companies.

By the time he became curious about his family’s past, most of the old-timers, including his father, were gone. In the 1970s, Marquez joined the Los Angeles Corral of Westerners, a group of professors, lawyers, and others dedicated to exploring the history of the West. They, as well as historians and fellow collectors, taught him how to sniff out choice images and documents.

“Looking North from 9th and Main Sts,” downtown Los Angeles, ca. 1890–1908; photograph by George W. Hazard.

Fortunately for his tight budget, Marquez began collecting before Californiana was in high demand. Sometimes for pennies, sometimes for a few dollars, he would purchase items that Huntington experts now consider to be pictorial gems—images of bygone adobes and trolley cars, streets and storefronts, pioneering residents, and early tourists.

Marquez found over time that he often knew more than the dealers about the treasures they were vending. “I’d pretend like it was just ordinary,” he says. “I’d buy it for a few dollars, but inside I was just totally excited. It’s their fault for not knowing what they had.”

Aerial view of the Santa Monica Municipal Pier and the adjacent Looff’s Pleasure Pier, showing the Blue Streak Racing Coaster, 1922. Photograph by Dunning Air.

Watts says she first met Marquez about 20 years ago as she began preparing for an exhibition about Los Angeles and water. “I was really bowled over not just by the amount of material he had but also by his expertise,” she says. “I developed a great affection for him.”

Whenever Suzanne Oatey, project archivist at The Huntington, queried him about images in his collection, she found that he could still extract obscure details from his encyclopedic memory.

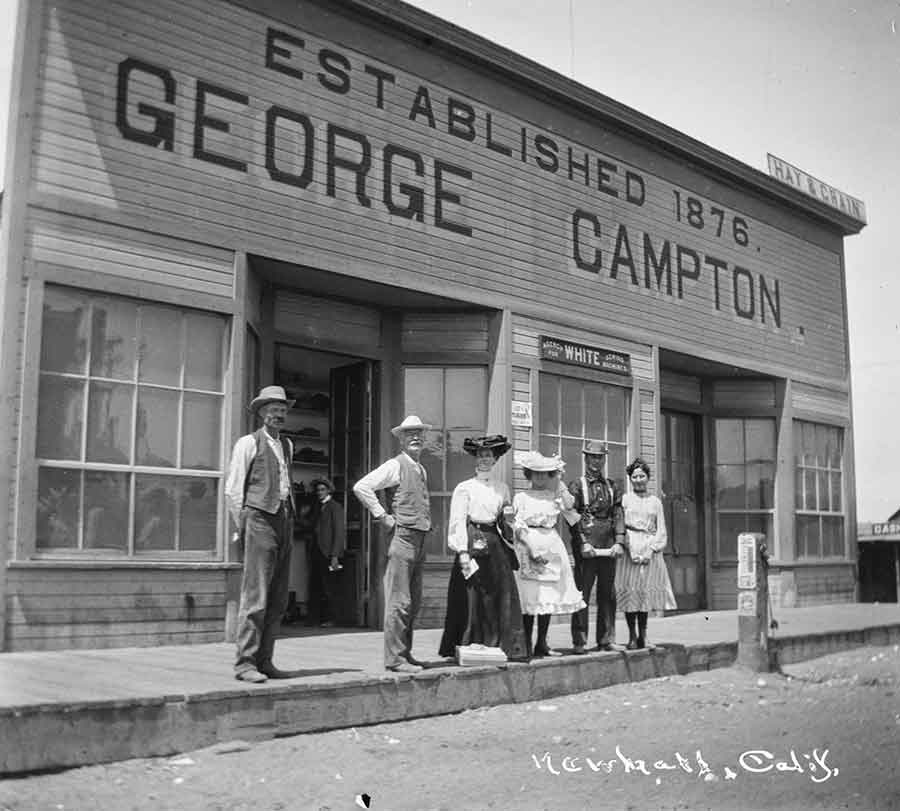

George Campton’s general store, Newhall, Calif., 1890s. Campton—thought to be second from left—was also the Newhall postmaster from 1877 to 1886. Photograph by George W. Hazard.

The collector himself took some of the most recent images. In 1983, he snapped color shots of the Santa Monica Pier as portions of it were being dismantled after a big storm.

“Ernie was doing his own documenting,” says Oatey, who spent 18 months organizing the collection. “He liked charting the passage of time and how things changed.”

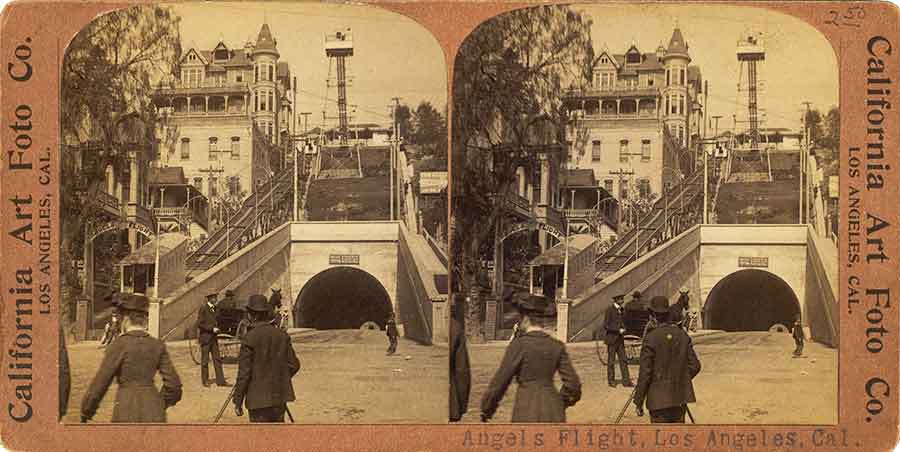

Angels Flight, Los Angeles, ca. 1902–8. The Angels Flight incline railway, which opened in 1901, is seen to the left of the Third Street tunnel, at the intersection of Hill Street in downtown L.A. One of the grand residences of Bunker Hill, the three-story Crocker Mansion, built in 1886, is seen at top left. Photographs by California Art Foto Company.

In fact, drawing on his extensive decades-spanning archive, Marquez wrote several of his aforementioned books about the region’s history, among them Port Los Angeles: A Phenomenon of the Railroad Era (Golden West Books, 1975); Santa Monica Beach: A Collector’s Pictorial History (Angel City Press, 2004); Port of Los Angeles: An Illustrated History from 1850 to 1945, with Veronique de Turenne (Angel City Press, 2007); and Noir Afloat: Tony Cornero and the Notorious Gambling Ships of Southern California (Angel City Press, 2011).

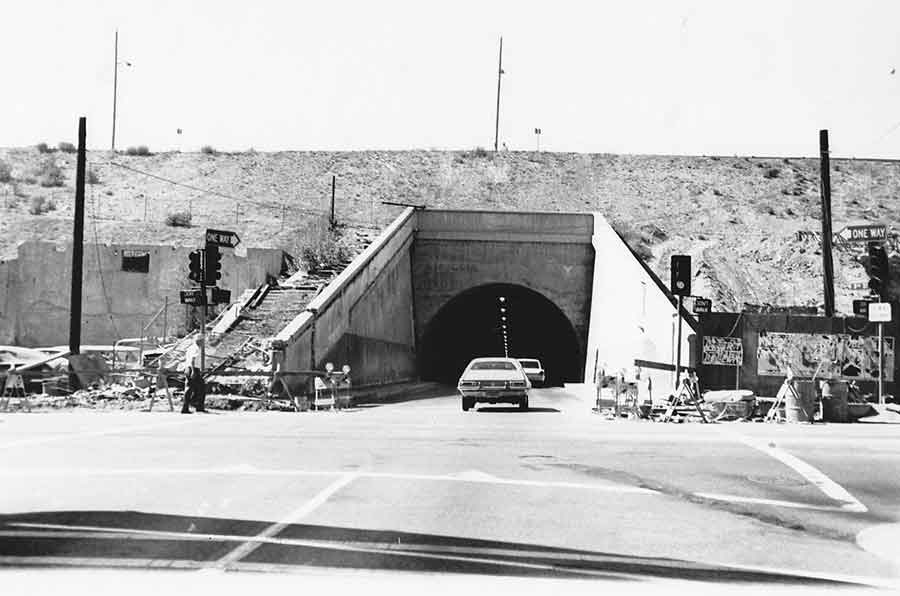

Angels Flight, photographed in early 1969, before its closure on May 18, 1969. Unidentified photographer.

On a more personal note, he penned and published Memories of Canyon School, 1930–1936 (2012), which features his own student artwork. Unbeknownst to him, his mother had squirreled away every creation. He found the items years after her death.

He is also hustling to finish an extensive history of Rancho Boca de Santa Monica. To help with that project, Marquez retained boxes of photos and other materials directly related to the rancho and his family. His family continues to be foremost in Marquez’s thoughts. Last year, he completed 34 decorative crosses for the graves in the small, historic Marquez Family Cemetery on San Lorenzo Street in Santa Monica Canyon.

Remains of Angels Flight, 1971. Unidentified photographer.

A few years ago, Marquez enlisted Michael Dawson, a rare-book and photography dealer with expertise in Southern California history, to appraise the collection. Dawson had seen bits and pieces in the past and was intrigued by the range of material. “The depth and breadth of his collection was more or less unrivaled,” Dawson says. “It’s such a wonderful and inclusive collection. Ernie was interested in businesses and infrastructure development. He was just way ahead of the curve.” Although Marquez’s early interest was in Santa Monica, Pacific Palisades, and the Malibu coastal area, his focus expanded to include the San Fernando Valley, downtown Los Angeles, San Pedro, and Pasadena.

Southern Pacific train entering Santa Monica, ca. 1878. Photograph by E. G. Morrison.

Images of the region’s early recreational areas, particularly along the coast in Santa Monica, “are going to deepen our understanding of precisely how tourism laid a foundation for what would become L.A.,” says Eric Avila, professor of Chicano studies, history, and urban planning at UCLA. The collection also includes more than 1,200 stereographs by the region’s most important early photographers and studios, including Carleton E. Watkins (renowned for his astonishing views of Yosemite), H.T. Payne, A.C. Varela, Francis Parker, and dentist-turned-chronicler William M. Godfrey.

A group of workers on the beach in Santa Monica, ca. 1903. The man third from the right is Felix Puertas, the maternal grandfather of Ernest Marquez, who writes, “The location was between the Santa Monica Pier and the Ocean Park Pier, looking north toward Ocean Park. There was a big storm in 1903 that washed out the old wooden boardwalk. It appears the workers are driving piles into the sand to replace the old boardwalk with a cement one.” Photograph by H.F. Rile.

Photographer Bob Plunkett, known for his souvenir postcards, is well represented with 827 negatives, mostly from the 1930s and 1940s (see cover). The images show residences of Hollywood actors, synagogues, churches, municipal buildings, auditoriums, and movie theaters, including the city’s first drive-in.

Historians have already begun to tap the trove. Last year, an environmental consulting firm based in Riverside received The Huntington’s permission to use several of Marquez’s images of the California Incline, a recently rebuilt roadway in Santa Monica, to illustrate a historical report.

Project archivist Suzanne Oatey (left), curator of photography Jennifer A. Watts (center), and Ernest Marquez at The Huntington in 2016. Photograph by Kate Lain.

Christopher Hawthorne, the architecture critic for the Los Angeles Times, says he is struck by “how much the photographs chip away at the familiar cliché that Los Angeles was organized around the automobile.”

“In fact,” he says, “L.A. was built around a marriage of convenience between the streetcar and speculative real estate development, whether at the level of the beach club or subdivision. You can see a city that is slowly filling in the gaps between one train line and the next, between one enclave or neighborhood and the next, all the way out to the coastline.”

Randy Young, a Pacific Palisades historian and photographer, encouraged his friend Marquez to sell the collection whole rather than peddle it piecemeal. Taken together, he says, these blocks and batches of images reveal valuable information.

Marquez and Watts in his garage in 2015. Photograph © Gary Leonard.

Even with his practiced eye, Young found himself doing double takes at some of the images, such as E.G. Morrison’s 1878 albumen print of passengers alighting in Santa Monica from cars of the brand-new Southern Pacific Railroad. Women in long dresses trudge through dirt, skirting stacks of wooden planks.

“You can almost smell the newness of the lumber,” Young says. “It’s like something out of a Sergio Leone western.”

Martha Groves is a freelance writer based in Los Angeles.