Artful Partnership

Posted on Sun., Nov. 13, 2016 by

A needlework treasure from the collection of Jonathan and Karin Fielding

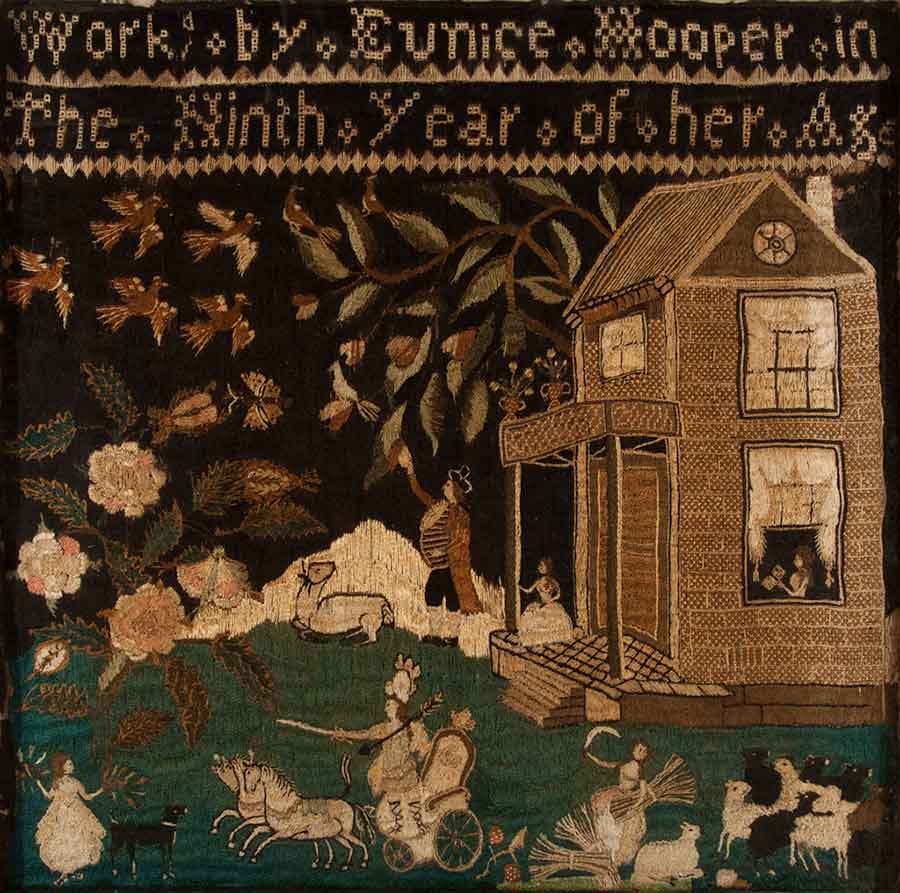

Eunice Hooper’s Sampler, ca. 1790. Silk on linen, 21 x 21 ¼ in. Collection of Jonathan and Karin Fielding.

The colorfully embroidered samplers produced in early America by girls between the ages of eight and 18 were typically the result of a creative partnership between a gifted teacher and a remarkably diligent student. A richly collaborative effort, these needlework compositions were based on designs sketched or blocked in by the teacher—sometimes in pencil—and subsequently stitched by her young pupil. Upon completion, these samplers were framed and displayed in the best parlor of the young girl’s home, where they could be seen and admired by family and visitors.

The immense pride felt by a young girl when completing her exactingly detailed needlework rings through a passage in Sarah Smith Emery’s Reminiscences of a Nonagenarian, written in the 1870s, more than 75 years after she had completed her own youthful composition: “The summer I was eight years old [1795] a Miss Ruth Emerson from Hampstead, N.H. [created a new, elite school]… Miss Emerson was a most accomplished needlewoman, inducting her pupils into the mysteries of ornamental marking and embroidery. This fancy work opened a new world of delight. I became perfectly entranced over a sampler that was much admired, and…became the wonder of the neighborhood.”

Left to right: Details depicting a pastoral landscape, a helmeted figure riding in a chariot, and a fall harvest, from Eunice Hooper’s Sampler, ca. 1790. Photograph by Kate Lain.

While young girls such as Emery proudly stitched their own names and ages into their samplers, their teachers’ names rarely appeared. However, through a careful analysis of subjects, recurrent themes, patterns, and decorative motifs, as well as stylistic analysis, historians today have been able to assemble groups of related samplers that are thought to have been designed by particular teachers. While the names of most of these teachers are still unknown, we now understand the critical role they played in the design and development of these compositions.

Among the most significant of these is a group of samplers made in the last decade of the 18th century in Marblehead, Mass., a prosperous coastal town north of Boston. Of this group, needlework scholar Betty Ring has written: “The incomparable samplers of Marblehead have no foreign counterparts and represent American girlhood embroidery at its best. Their lively designs and perky verses captured the spirit of optimism in the new nation as well as the climate of their town…The existence of Marblehead samplers as a group was unknown before 1980, but they now compose one of the most spectacular recognizable groups of New England needlework.”

Detail of a woman reading in a Georgian-style house, from Eunice Hooper’s Sampler. Photograph by Kate Lain.

These compositions, most of which have richly embroidered black backgrounds, feature vivid images of everyday life: a woman reading inside the window of a Georgian-style house, a handsomely dressed young couple standing on a porch or in a pastoral landscape, or a fall harvest scene suggesting abundance and prosperity. These commonplace moments in daily life are often combined with fanciful images of idealized neoclassical subjects, such as a helmeted figure riding in a chariot, a maiden dressed in classical robes and sandals, or the figure of Cupid with his arched bow and arrow. In these compositions, such encounters, both real and ideal, occur beneath a sky teeming with birds and butterflies in a paradisiacal landscape filled with lush blossoms and plants. Several of the specific subjects depicted in these samplers recur in work stitched by different girls, suggesting that their teacher maintained and reused design templates, offering her young pupils a choice among a set repertoire of themes.

Although the name of the instructor responsible for the design of this Marblehead group is not known, Betty Ring suggests that she may have been Martha Tarr Hanover Barber (ca. 1735–1812). Barber ran a school for young girls in Marblehead during this period, and Ring feels it quite likely that she was the talented designer who drew these imaginative compositions.

Harold B. Nelson, curator of American decorative arts at The Huntington, holding Eunice Hooper’s Sampler. Photograph by Kate Lain.

Jonathan and Karin Fielding—lead donors for the recently opened Fielding Wing of the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art—are fortunate to have in their collection an exquisite and extremely rare sampler from this Marblehead group. It is currently being shown as part of the new wing’s inaugural display of more than 200 works from the Fieldings’ collection of 18th- and early 19th-century American art works.

As she proudly stitched in big, bold letters at the top of her sampler, it was “work’d by Eunice Hooper in the ninth year of her age.” Hooper (1781–1866), daughter of Samuel Hooper and Elizabeth Russell Trevett Hooper, was a member of a prominent Marblehead family. Her sampler, made about 1790, combines a remarkable level of naturalistic detail with sheer fantasy, and it is among the finest of the samplers stitched in that town. With its image of a two-story house and porch, viewed from the side, Hooper’s composition is closely related to one stitched by Sukey Jarvis Smith, a young girl from Bristol, R.I., who visited her sister in Marblehead in 1791. The two young girls undoubtedly studied with the same teacher, who gave them similar needlework designs.

An adept needleworker in her youth, Eunice Hooper later married her cousin John Hooper in 1799, and together they raised a family of nine children. Remarkably, the elegant high-waisted gown that she wore at her wedding survives today and is now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Harold B. Nelson is the curator of American decorative arts at The Huntington.