Trees in a Time of Drought

Posted on Sat., Oct. 17, 2015 by

The Huntington serves as ground zero in a race to research, and ultimately kill, the pests that threaten Southern California's trees

The leaf canopy of a healthy cork oak (Quercus suber), with its wonderfully craggy bark, provides green shade for visitors to The Huntington during a time of intense drought. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

Four years of historic drought. Restricted water use. The Darth Vader of tree pests and assorted other destructive bugs, diseases, fungi, and root rot. To protect and maintain the health of the thousands of trees on its property, The Huntington faces urgent challenges on multiple fronts.

During a golf-cart tour, The Huntington's arborist Daniel Goyette spots one victim of California's sustained drought: a dead pine tree rising from a stand of leafy carrotwoods. Minutes later, he indicates a Chinese mahogany, between 10 and 20 years old, that has succumbed and is slated for removal.

"As we get further and further into the severe drought," Goyette says, "we're seeing different species here start to die off. The European white birch trees were the first to start to go. Alder trees. Some Southern magnolias are going."

Over the next half hour, Goyette points out numerous areas of concern. Water-intensive stands of bamboo. Japanese cedars, turning brown without the moisture they are used to in their native country. Some historic redwoods, too, are showing their distress.

"Lack of humidity, lack of rainfall," Goyette says. "They need a deep soaking, and that's the only thing we can replicate well, by getting some drip irrigation out along the drip line of those trees and allowing it to percolate into the ground."

A combination of drought and increased heat seems to be creating a "tipping point" for the state's native oaks as well, says Rosi Dagit, senior conservation biologist for the Resource Conservation District of the Santa Monica Mountains and an arborist for the California Oak Foundation (as well as author of the children's book Grandmother Oak).

Oaks are "inordinately well-evolved to adapt to drought conditions," she says. "What's changed is the number of days that are over 90 degrees. You can have lack of rain for months on end, and if the temperatures are not extreme, that is one level of stress. Increase the temperatures and number of days and months over which those high temperatures are found, and you've added a whole other layer of stress."

The stubby remains of an oak tree at The Huntington, its dying limbs lopped off, illustrate Dagit's point. "Now it is more a tall oak shrub than an oak tree," Goyette says. "At some point, we're going to have to say we've spent enough time and energy on it. Is the tree worth saving? Can we put something in its place that will be less susceptible to drought and pests?"

Losing it will be "a sad day," he says.

Daniel Goyette, The Huntington's arborist, measures the circumference of a diseased Liquidambar's trunk and takes notes on its condition before the tree is removed. Yellow stains on the trunk indicate the presence of the destructive Fusarium fungus introduced by the polyphagous shot hole borer, a tiny invasive beetle. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

Like home- and landowners up and down the state, The Huntington is under a mandate to cut water usage—in its case, by a third. It is in the process of installing water-conserving drip irrigation systems, part of a conversion that includes eliminating sections of lawn and revamping current irrigation methods.

Watering restrictions translate to 15 minutes of above ground irrigation, two days a week, Goyette says. Any new drip irrigation system must take into account the varied amounts of water required by different species of trees, their location, and the competition for water that will come from nearby plants. And because windblown dirt and dust remain on dry leaves, inhibiting life-sustaining photosynthesis, some overhead irrigation must continue.

"We're doing our best to irrigate within the guidelines we've been given," Goyette says. "We're in reevaluation mode right now."

(Water limits are a concern, too, for The Huntington's Valencia orange and avocado groves and recently established grapevines. Since 2011, more than 81,000 pounds of the Valencias have gone to Food Forward, picked by the nonprofit organization's volunteers for distribution to charitable groups across Southern California.)

As a microcosm of trees and plants that grow all over the world, The Huntington must also maintain a meticulous lookout for harmful insects, bacteria, and diseases on its grounds—and monitor those that turn up in surrounding urban, park, and wild landscapes.

"Unfortunately, in the fourth year of drought," says Tim Thibault, The Huntington's curator of woody plant materials, "we've got some significant pests on the grounds here."

"It's a challenging situation," he says. "We have trees that are already drought stressed, so they have pests and disease; in turn, the continued drought stress is making the problems with those pests worse."

Among them: the twig girdler (it gnaws the ends of tree branches), the defoliating lerp psyllid (a eucalyptus pest), spider mites, root rot fungi, and the Asian citrus psyllid, which can vector bacteria, but "thankfully," Thibault, says, "it is not that much of a problem here." More serious, he feels, is a drought-driven infestation of the California five-spined ips, or bark beetle.

In an overgrown area north of the Chinese Garden—where there are plans to replicate a mountainous pine forest in China—truncated, barren pines produce an uncanny graveyard feel. Deodars have succumbed to the drought, but two Canary Island pines and a Torrey pine are victims of the opportunistic ips.

Left: The black holes and chambers in this box elder's wood indicate damage caused by the polyphagous shot hole borer. Right: Nursery manager Dan Berry holds five polyphagous shot hole borers—each smaller than a sesame seed—in the palm of his hand. Photographs by Lisa Blackburn.

"We've been trying to remove trees as they are identified as being affected," Thibault says, "but we're at a point now in the Los Angeles Basin where we've got both drought-stressed trees and a population of bark beetles that is high enough to take them out, even if they weren't drought stressed."

"It's a bad time to be a pine tree," he adds.

Bark beetles, says Tom Coleman, a Southern California forest entomologist with the USDA Forest Service, "kill more trees than wildfire does every year, basically throughout North America. When a healthy tree has enough water and enough resin, it can push these beetles out when they start to attack. When they're extremely stressed out, they can't do that."

Aerial surveys of forest areas in Southern California reveal an all-you-can-eat bark beetle smorgasbord: an estimated 2 million dead trees, mostly pines, lost to the drought.

With some pests, vigilance and tried-and-true remedies aren't enough.

Along a winding path through The Huntington's Desert Garden, it is hard to miss: the enormous stump of a sycamore, one lone branch remaining of its once-lofty height of 80 feet. After some 100 years of growth, the venerable tree was felled by an insect smaller than a sesame seed: the polyphagous shot hole borer.

This tiny invader, a new species of ambrosia borer beetle not identified until 2012, is a carrier of pathogenic fungi. It has wiped out all but one of The Huntington's box elders, and has oaks, sycamores, and numerous other tree species in its indiscriminate sights.

It is spreading its destruction over wide and growing swaths throughout San Diego, Los Angeles, and Riverside Counties. For plant pathologists and entomologists from the University of California, Riverside, The Huntington, home to virtually every tree species of interest to the bug, has become ground zero for research as they work feverishly in collaboration with Thibault, his Huntington colleagues, Coleman, and others to find ways to curb or neutralize the threat it poses.

"This beetle was first identified as coming into California as the tea shot hole borer," says Timothy Paine, UC Riverside professor of entomology. "It's been in the state for probably 10 years or so, but it wasn't recognized as a problem here until two or three years ago."

Plant pathologist Akif Eskalen, head of UC Riverside's Eskalen Lab, made the link in early 2012 when he was asked to examine a South Gate homeowner's damaged backyard avocado tree. Eskalen found the trunk riddled with tiny holes and stained by an unfamiliar fungal infection.

UC Riverside entomologist Richard Stouthamer's DNA analysis of the beetle responsible showed that, while morphologically identical to the tea shot hole borer (a wide-ranging Asian ambrosia beetle) and of the same genus, it had "14 percent genetic differences in the so-called barcoding gene." These variations, Stouthamer said, proved it to be a separate species.

DNA fingerprinting would show, too, that this same species, deemed a threat to California's multimillion dollar avocado industry, previously had wreaked havoc in Israel's avocado orchards (where it had also been misidentified as the tea shot hole borer.)

Left: Pines north of the Chinese Garden that succumbed to the bark beetle (also known as the five-spined ips) had to be cut down and removed. Right: Gardener Jose Lopez views Fusarium damage in a cross-section of a Liquidambar tree that fell victim to the polyphagous shot hole borer. Photographs by Lisa Blackburn.

When Eskalen began a survey of trees affected by the newly identified and newly named polyphagous shot hole borer, an effort first funded by the California Avocado Commission, his scouting led to The Huntington. (The Los Angeles County Arboretum is another research site for the UC Riverside scientists.)

"We had called [Eskalen] out to look at our avocados," Thibault says, "and we had a large English oak by the entry that was dying and asked him to look at that." The culprit in both cases was Fusarium dieback, vectored by the poly-phagous shot hole borer through the pathogenic species of Fusarium (fungi) that it carries.

"That's when Akif got really interested, and my life changed," says Thibault. As a result of their joint findings, Thibault coauthored with Eskalen, Stouthamer, and other UC Riverside scientists a paper on the beetle and its symbiotic Fusarium, published in the July 2013 issue of Plant Disease, a journal of the American Phytopathological Society.

As the research continues, other surprises have turned up.

Stouthamer has found that the polyphagous shot hole borer in Los Angeles differs genetically from the San Diego invaders. Eskalen's recent research reveals that it also carries and disseminates not one but three types of fungi (Fusarium euwallaceae, Graphium sp., and Acremonium sp.). The beetle population in San Diego carries two.

"The Los Angeles beetle has spread from Sylmar to now close to Dana Point," says Stouthamer. "At some point, the two are going to meet, and we're worried about that, because then you can get new combinations of beetles and fungi. And we don't know what that's going to do."

Essentially "fungi farmers," these beetles are not wood eaters but symbiotic vectors for the pathogenic fungi they carry. Inoculating the tree with fungal spores, they grow the fungi—the sole diet of both adults and larvae. In the process, the fungi colonize the tree's vascular tissues and compromise, often fatally, its ability to transport water and nutrients from its roots.

(Signs of the beetle/fungi presence include leaf discoloration, branch die-off, moist, dark staining and/or whitish powdery exudates around the tiny, precision-drilled holes.)

"In the sense that you have the perfect storm, this beetle is the perfect pest," says Stouthamer. Once in the tree, it is inaccessible, and the compromised transport system inhibits pesticides or fungicides from reaching either the beetle or its source of nourishment.

The search for an effective pesticide and/or a parasitic fungus, however, is still on. "There are a lot of different ways we may be able to kill these darn things," Stouthamer says, "but it's a process that takes time. In the meantime, 100-year-old sycamores go."

Tim Thibault (left), curator of woody plant materials at The Huntington, and Richard Stouthamer, entomologist at University of California, Riverside, collect polyphagous shot hole borers from odor-emitting funnel traps to estimate the size of their population. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

Determining what effect, if any, the drought has on the infestations is another area of exploration. UC Riverside entomology graduate student Colin Umeda is running an experiment in a field at The Huntington to see if the beetle is drawn to well-hydrated or drier trees. He has brought in 64 young box elders, staked them out in an inviting grid, and is using tensiometers to measure soil moisture levels.

Box elders are "one of the most susceptible hosts for the beetle," says Paine, chosen because "we want to be sure the beetles are going to attack at some point. It's unfortunate as far as the tree goes, but it does let us get additional information that we might not be able to get otherwise."

Umeda is also monitoring the rate of beetle development under different temperatures in a quarantine facility at the UC Riverside Center for Invasive Species Research to "identify which temperatures are the limits that the beetle can reproduce in, and in which the beetles perform especially well," he says.

The discovery of a bait attractive to the beetles in their flying phase enabled the creation of odor-emitting funnel traps at The Huntington. Counting the number of beetles in the traps is providing an estimate of beetle population development.

("We've also tried some 'things that are so crazy they just might work,' " Thibault says. Bio-acoustical control, for example, involves the playback of recorded sounds made by the beetles; researchers at Northern Arizona University have had some success with this bark beetle control in their laboratory.)

While it isn't clear how the polyphagous shot hole borer migrated to Southern California via two separate routes, the human factor is likely, Paine says.

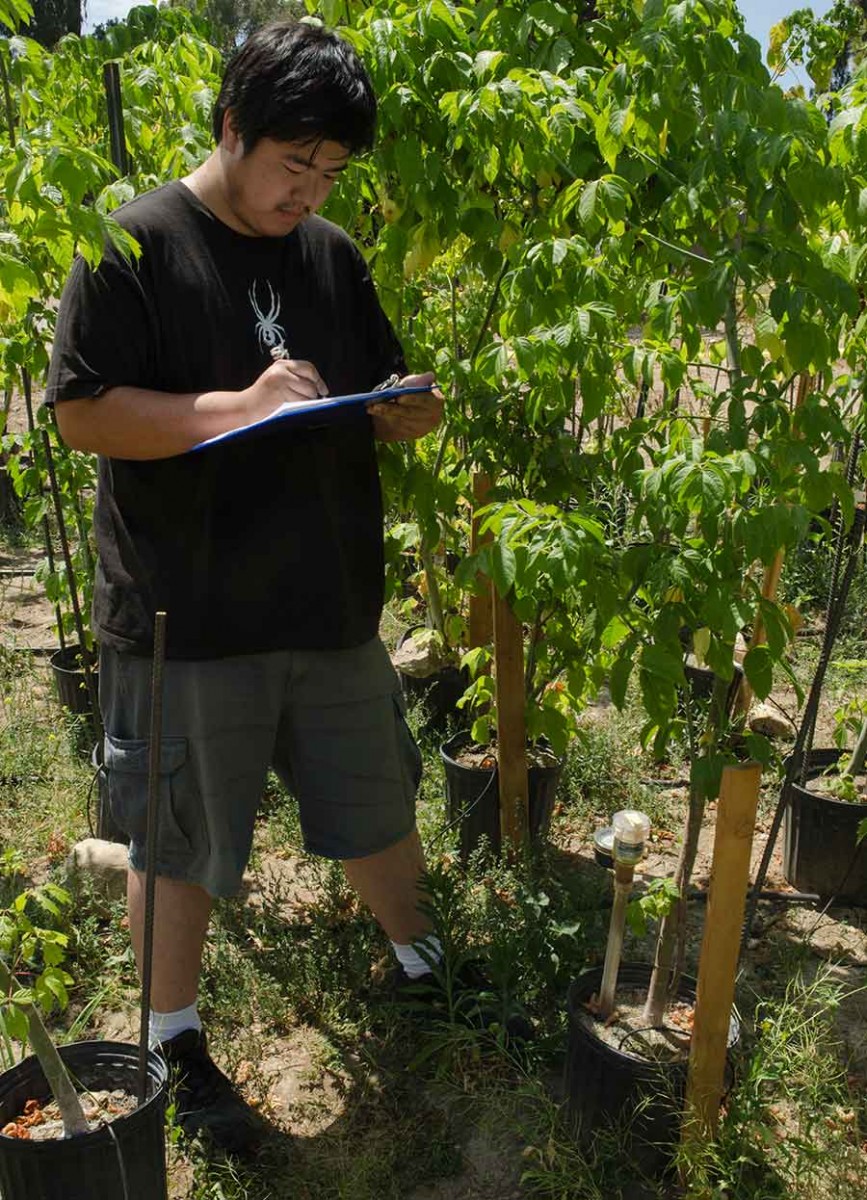

Colin Umeda, an entomology graduate student at UC Riverside, conducts an experiment with 64 young box elders at The Huntington, recording soil moisture levels to determine if polyphagous shot hole borers are drawn to well-hydrated or drier trees. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

"People don't recognize what serious problems they might cause by not being careful about bringing in plant material from overseas. I mean, the signs at the international terminals at airports are not there by accident."

At present, just under four dozen tree species are the beetle's favored reproductive hosts. The number of tree species that it targets? More than 350 and counting.

There is one promising development. During trips to Vietnam and Taiwan—home to genetic matches for the L.A. and San Diego polyphagous shot hole borer populations, respectively—Eskalen, Stouthamer, and Thibault have found species of a predatory wasp and of a fly that seem to target this beetle. The insects require further study in the field and in the lab (a process of years, not months, considering quarantine and permission requirements), but Stouthamer has hopes that the wasp, in particular, may be the key to substantially reducing Southern California's beetle populations.

(UC Riverside, which has a long history with plant management through biological controls, has also identified a parasitic wasp that successfully targets the Asian citrus psyllid, a major threat to California's citrus industry and home growers.)

Long committed to the limited use of chemical pesticides, The Huntington would certainly prefer a biotic solution, Thibault says.

"We've got 700,000 visitors a year, not to mention concerns for our own safety," he points out. "The current theory in integrated pest management is to spray as little as possible, and we do as little as we possibly can."

Meanwhile, Goyette canvases the gardens daily for drought and pest damage. In any given week, he walks and drives—via golf cart—around all 207 acres of The Huntington property, "just to be sure nothing new is dying, staying aware of what's happening."

"Something I need to look at now," he says, "is a willow in the Shakespeare Garden. Apparently there is something attacking that. It could be," he adds with optimistic cheer, "just a nuisance pest that will come and go."

For his part, Thibault, even as the hunt for a solution to the polyphagous shot hole borer and its killer fungi continues with crime scene urgency, is concerned about two bad bugs not yet on site: the South American palm weevil—"it is right on the border in Tijuana," he notes—and the gold-spotted oak borer.

The latter "is now in Orange County, and there's a continuity of oak trees, coupled with the flight range of the insect, that could ladder it to us."

"And you never know," Thibault says, "when somebody is going to throw a load of infected firewood in the back of their pickup and bring it right to Pasadena."

Lynne Heffley is a freelance writer based in South Pasadena, Calif.