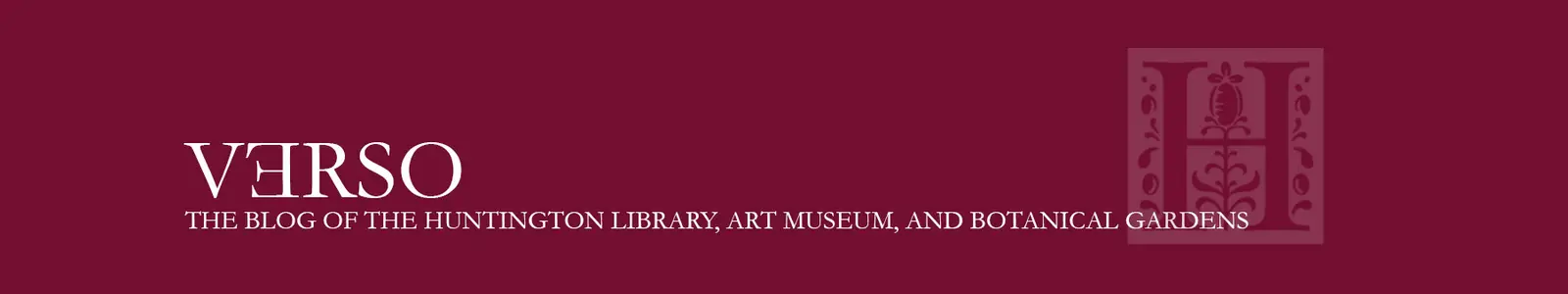

Home Run Polka. Sheet music, 1867. Printed by L. N. Rosenthal, Philadelphia, Pa., color lithograph on paper, 13½” x 10½”. This illustrated cover shows a loose interpretation of the Massachusetts Game rules for laying out the grounds. Two key features are depicted: a square field and stakes for bases. Gift of Jay T. Last. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The Fourth of July conjures up images of parades, backyard barbecues, fireworks—and, for some folks, baseball. The sound of “Play ball!” recently encouraged a few Huntington curators to explore our collections for items centered around the sport. What we found just might change what you know about the history of the game.

Baseball has helped shape U.S. culture since the 1850s, when amateur clubs first formed in the northeastern states. Clubs played rousing “matches,” as games were then called, cheered by spectators and reported in public journals. Baseball is an “exciting sport and healthful exercise at a trifling expense,” wrote one New Englander in 1858.

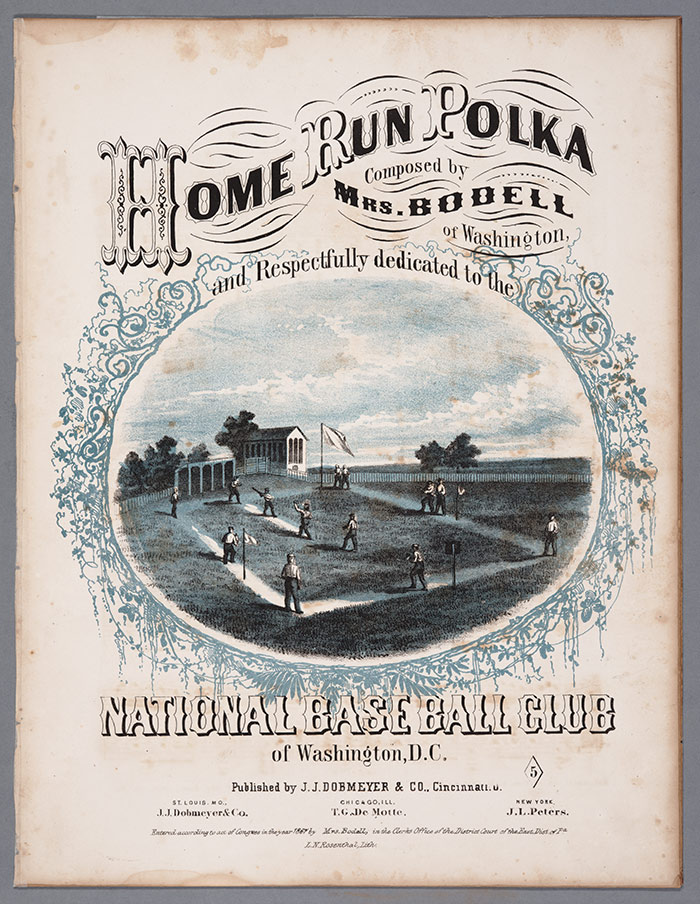

The Base Ball Quadrille. Sheet music, 1867. Printed by John H. Bufford’s Lith., Boston, Mass., color lithograph on paper, 13¾” x 10½”. Composer Henry Von Gudera “respectfully dedicated” this musical composition to the Tri-Mountain Base Ball Club of Boston. Curiously, the Tri-Mountains would become the first of the organized clubs playing the Massachusetts Game to abandon it in favor of the New York Game. Bases, similar to today, appear in the foreground and background of the image, indicating the New York-style rules. By contrast, the Massachusetts Game used stakes to mark bases. Gift of Jay T. Last. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Regional interest grew, aided by publicity. Promoters posted broadsides in neighboring towns to announce upcoming matches, and newspaper publishers spread the word by printing game summaries for their readers. By the 1860s, baseball had inspired such popular tunes as “Home Run Polka,” “Catch It on the Fly,” and “The Base Ball Quadrille,” which families could play at home on their parlor pianos. These lively sheet music melodies, enhanced with illustrated covers, got everyone into the spirit of the game.

The first professional baseball league was launched in 1871, and the game of baseball became wildly popular. Teams from as far west as Cleveland, St. Louis, Fort Wayne, Rockford, and Chicago banded together with their eastern rivals in 10 cities, extending from Boston to Washington, D.C. Meanwhile, the public crowned baseball the champion of outdoor sports. “The fascination of the game has seized upon the American people, irrespective of age, sex or other conditions,” claimed Harpers’ Weekly in 1886. One year later, Walt Whitman dubbed the sport “America’s game.”

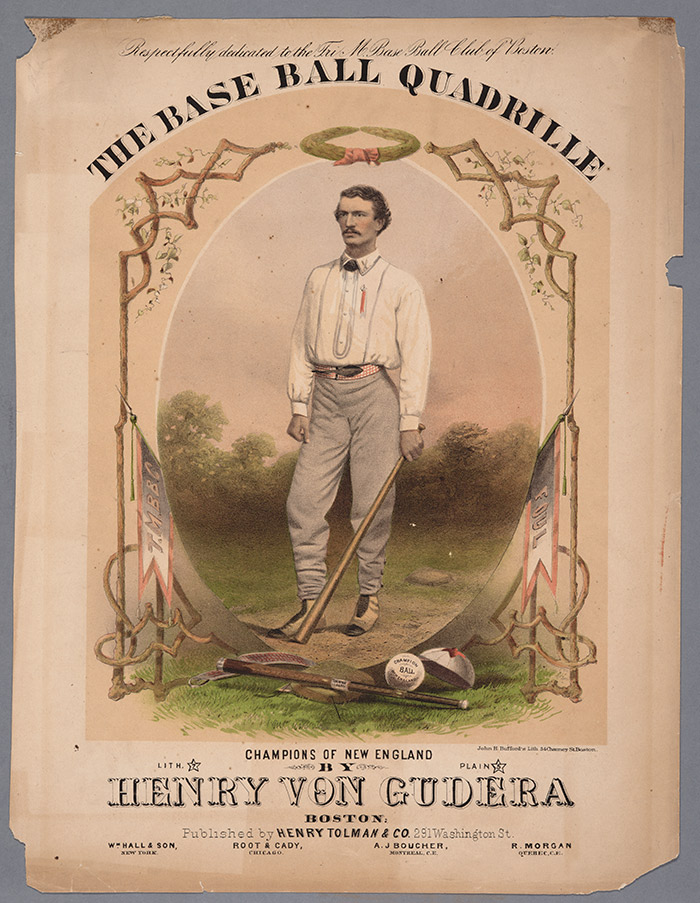

Diagram of the Massachusetts Game square from The Base Ball Player’s Pocket Companion, 1859, published by Mayhew & Baker, Boston, Mass. Rules for laying out this field included bases spaced 60 feet apart and a pitching distance of 30 feet between the thrower and the striker. Both dimensions were smaller than those used for the New York-style diamond field. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

But here’s the real eye-opener. A volume from The Huntington’s collection of rare books reveals that there were two very different styles of playing the game in the antebellum U.S. In 1859, Boston publishers Mayhew & Baker issued a 36-page illustrated guide, The Base Ball Player’s Pocket Companion. This miniature bible of sorts cites rules and regulations for forming clubs, as well as directions for playing the “New York Game” on a diamond, as it is today; and the “Massachusetts Game,” played on a square!

The Massachusetts Game, as adopted by the Massachusetts Association of Base Ball Players on May 13, 1858, was considered the favorite and principal game played throughout New England. By 1859, 20 clubs from across Massachusetts belonged to the association. According to the Pocket Companion, the only essential equipment they needed to play a game (besides a ball) was “a bat-stick, and four wooden stakes for bases. The game is commenced by staking off a square of 60 feet for the bases, and measuring the distance of 30 feet from the thrower’s to the striker’s stand.”

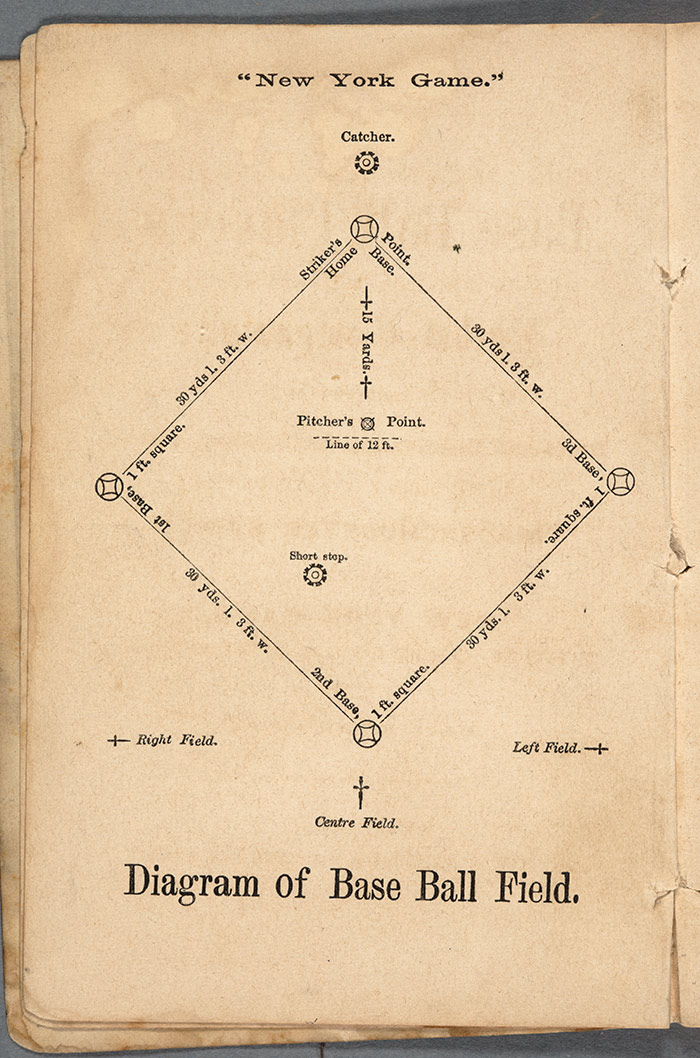

Diagram of the New York Game diamond from The Base Ball Player’s Pocket Companion, frontispiece, 1859, published by Mayhew & Baker, Boston, Mass. This layout called for larger dimensions than the Massachusetts-style square field. Bases were 30 yards apart, as they are today, and the pitching distance stretched to 45 feet. Not until the 1890s would this distance extend to 60 feet 6 inches, the current standard. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

On March 19, 1859, the National Association of Base Ball Players convened in New York to adopt its latest rules and regulations. The Pocket Companion described the field for the New York Game in a way that closely resembles today’s diamond: “. . . the bases must be four in number, placed at equal distances from each other, and securely fastened upon the four corners [of the field], whose sides are respectively thirty yards. The first, second and third bases shall be canvass bags painted white, and filled with sand or saw-dust; the home base . . . to be marked by a flat circular iron plate, painted or enameled white.”

Each of the two styles had its adherents. Fans of the Massachusetts Game claimed that their version was more exciting to play and watch because it created a constant supply of base runners and plenty of scoring. Foul territory did not exist, encouraging strikers to hit the ball in any direction, and first base was just 30 feet away from a striker, who stood halfway between it and “home.” Ultimately, however, the New York style of play was adopted as our national game and became the forerunner of modern baseball. The square field of the Massachusetts Game remains a curious relic of our popular culture.

Base Tender. From The Base Ball Player’s Pocket Companion, 1859. Published by Mayhew & Baker, Boston, Mass. 5½” x 3¾”. One of four woodcut illustrations of Massachusetts Game players; the others are titled The Thrower, The Striker, and The Catcher. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

David Mihaly is the Jay T. Last Curator of Graphic Arts and Social History at The Huntington.