Melencolia I, 1514, on loan from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, is one of 33 engravings by Albrecht Dürer that are on view in a small exhibition in the Works on Paper Room. Together with Knight Death and the Devil (1513) and St. Jerome in His Study (1514), the three large and ambitious engravings are now known as the “Meisterstiche,” or Master Prints.

In a small upstairs room in the Huntington Art Gallery, you will find the secret of how to turn common metal into gold. Or an example of Renaissance Sudoku. Or one of the earliest uses of subliminal advertising. Or perhaps something not yet discovered by the thousands of people who have analyzed Albrecht Dürer’s engraving Melencolia I (above).

The print, on loan from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, is one of 33 on display in “Albrecht Dürer: The Master of the Black Line,” a spotlight exhibition that includes small woodcuts as well as large and ambitious engravings. Melencolia I is the engraved equivalent of the Zapruder film, the Voynich Manuscript, and the first half hour of the movie Momento rolled into one.

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) was neither a mystic nor a prognosticator, but rather a master 15th-century printmaker who had the good fortune of enjoying tremendous success and recognition during his lifetime. Apprenticed at age 15 in Nuremberg, he went on to study extensively in Italy, befriending and impressing Renaissance masters. By the time he was in his twenties, his work was well known throughout Europe.

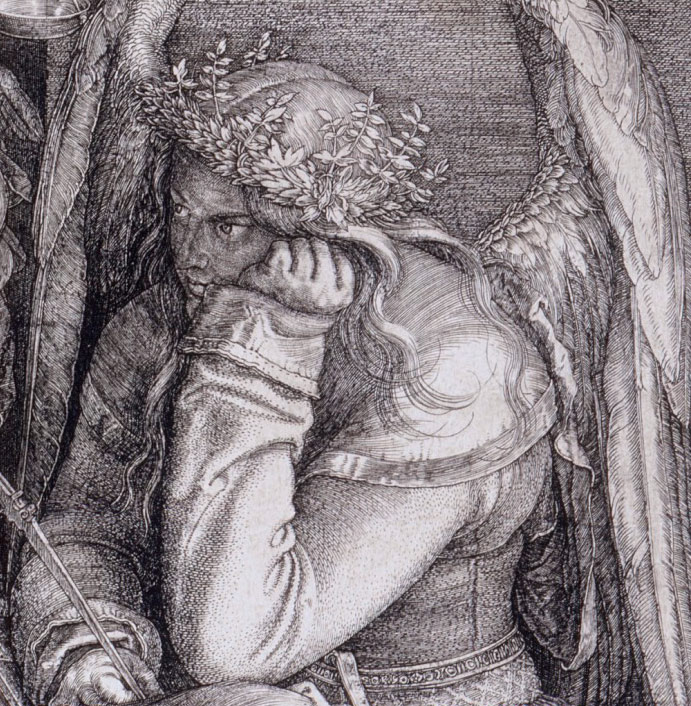

The central character in Melencolia I is a winged female figure slumped, her head in her hand, her face dejected and half hidden.

It is worth noting that his relatively quick rise to popularity was due in part to his chosen medium. Printmaking allowed for multiple, portable copies; some legitimate, some not. The downside to this mass distribution was the ease of forgery, and Dürer was a lucrative target. Marcantonio Raimondi, an overly ambitious Italian printmaker, stole Dürer’s intricate designs line for line and sold them for the same price, igniting this tirade from the artist:

“Hold! You crafty ones, strangers to work, and pilferers of other men’s brains. Think not rashly to lay your thievish hands upon my works. Beware [pilfering]…and bear in mind that if you do so, through spite or through covetousness, not only will your goods be confiscated, but your bodies also placed in mortal danger.”*

In what can be considered one of the earliest known copyright cases, Dürer obtained an injunction—but only against the unauthorized use of his well-known “AD” insignia. His artwork was fair game.

Knight Death and the Devil, 1513, engraving. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, Edward W. and Julia B. Bodman Collection.

Why all of the thievery? Dürer’s prints were highly coveted and his skill unmatched, as evidenced in the prints on display, which brings us back to the riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma, that is Melencolia.

The central character in the print is a winged female figure slumped, her head in her hand, her face dejected and half hidden. So far, not mysterious. But take a look at some of the items that surround her:

- A plaintive bat holding a banner that reads “Melencolia”

- A bell, a balance, and an hourglass

- A purse and keys

- Carpentry tools and a ladder

- A blazing comet and a rainbow

- A forlorn dog

- An orb and a polyhedron

- A “magic square” of numbers in which all rows add up to 34

For Dan Brown fans and armchair detectives, this is fertile ground for interpretation and speculation. Theorists have purported there is a code hidden in the etchings of the belt indicating deceased relatives, and that the ladder and the hourglass were symbols of alchemy, possibly pointing to a long-sought formula.

In the end, the accepted interpretation of the image is not quite as exciting, but one many of us can relate to: the melancholy of the creative process.

St. Jerome in His Study, 1514, engraving. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, Edward W. and Julia B. Bodman Collection.

“Why is it that all those who have become eminent in philosophy or politics or the arts are clearly of a melancholic temperament?” Aristotle asked in the 4th century. By Dürer’s day, it was commonly believed that creative genius and the pursuit of knowledge were characteristics of the melancholy temperament.

Why would one of the most successful printmakers of his day choose this as his subject? Perhaps the melancholy he drew from was not due to unrealized success, but rather in having achieved success and then realizing there was still more to do, that the struggle was never-ending.

Almost until the end of his life, Dürer pursued creative perfection, exploring new techniques and subject matter, the geometry of composition and form, and the interplay of the religious and the secular, in all manner of mediums. Stop by the Works on Paper room upstairs in the Huntington Art Gallery to commiserate with Dürer’s melancholy muse and view 32 additional images that testify to his ability to overcome artistic inertia.

“Albrecht Dürer: The Master of the Black Line” is on view in the Works on Paper Room of the Huntington Art Gallery through Aug. 25, 2014. It is curated by Kristoffer J. Neville, assistant professor of art history at the University of California, Riverside. All but one of the 33 works are from The Huntington.

*Notes and Queries: A Medium of Inter-Communication, Fourth Series, Vol. 2, 1868, pg. 508.

Matt Stevens is editor of Verso and Huntington Frontiers magazine.