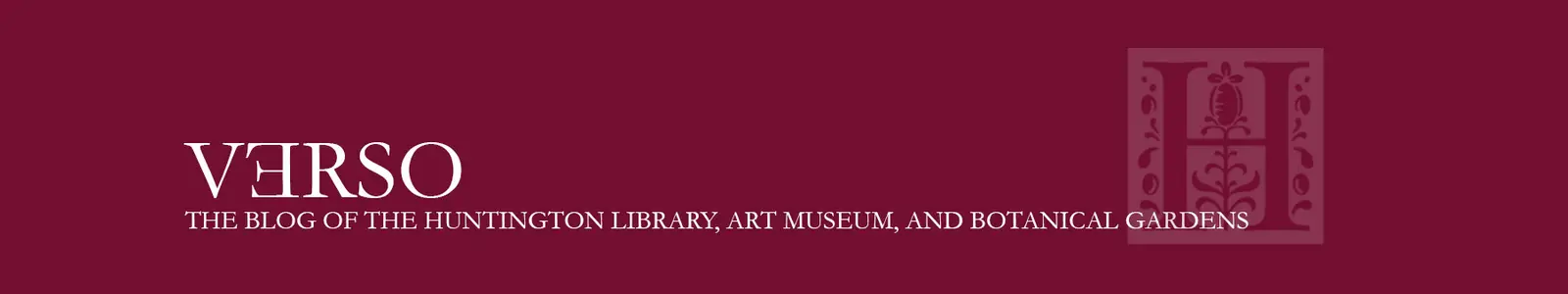

The title page of the first edition of Paradise Lost, 1667, by John Milton (1608–1674). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The Ridge Lecture in Literature, which I’ll deliver at The Huntington’s Rothenberg Hall on November 1, 2017, is an opportunity to celebrate the 350th anniversary of the first publication of John Milton’s Paradise Lost in 1667. It also gives me the opportunity to assess the daring originality of the greatest epic poem in the English language and one of the most influential works of English literature—a brilliant reimagining of the Bible’s story of the fall of humankind and its tragic consequences.

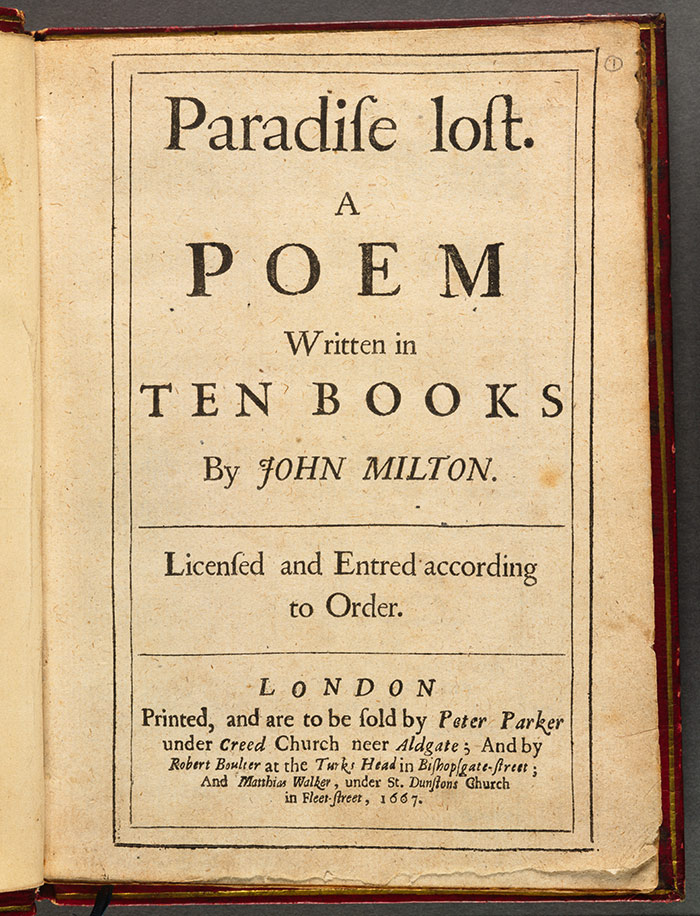

Milton first published Paradise Lost in 10 books. He then published another edition in 1674 consisting of 12 books, the version familiar to most readers. I’m currently editing a new Oxford University Press edition of Paradise Lost, which will include, for the very first time, versions of both. The first edition rarely receives the attention it deserves. The Huntington possesses no less than 13 copies of the poem’s 10-book edition.

When I discuss the differences between the poem’s two earliest editions, I’ll stress what was revolutionary about the poem. Its focus was not on national, legendary, or martial British history, as one might expect from an epic written in English, but on a topic of broader appeal—the biblical story of the fall of Adam and Eve.

The opening lines of Paradise Lost, 1667, by John Milton (1608–1674). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

As a godly republican writer who resisted the English monarchy, Milton became increasingly disenchanted with national politics. Yet when it came time to put his thoughts into verse, he settled on a more universal theme based upon the Bible. The story of the temptation of Adam and Eve allowed him to transcend contemporary and topical political controversies (or at least treat them more obliquely), while enabling him to explore, in imaginative ways, major political and religious issues, including political tyranny and religious freedom. His biblical subject was not only historically sound, but international in interest.

This explains why Paradise Lost could appeal to a more general readership—after all, what had greater appeal for Milton’s Protestant audience than retelling the biblical story of humankind’s first fall? It also spoke to religious Dissenters, like Milton himself, who felt they too had “fallen on evil days” (Paradise Lost, Book 7, line 25), when the Stuart monarchy and Church of England were restored in 1660.

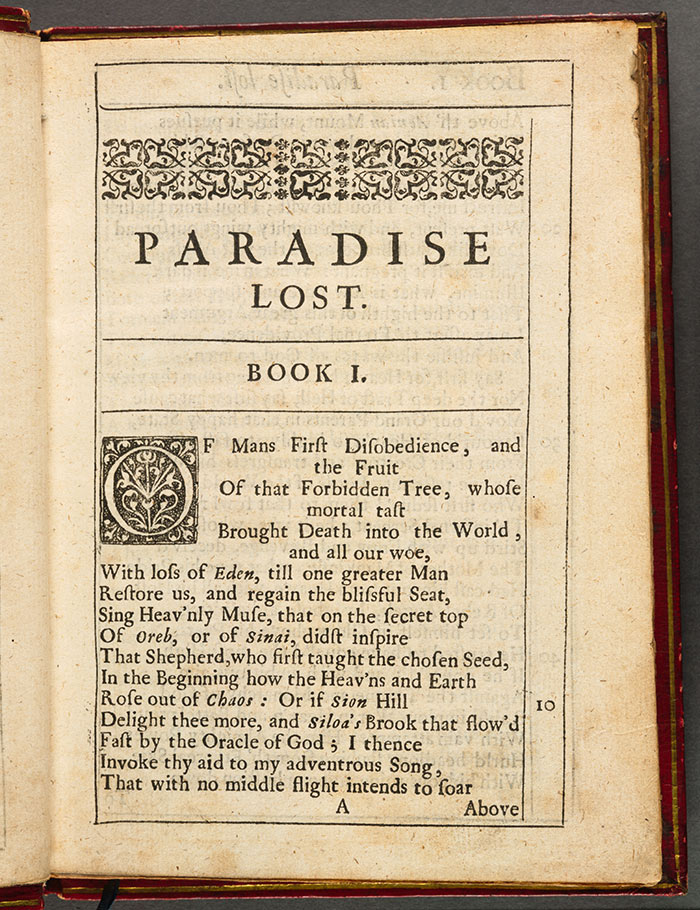

By the time the poem was published in its richly illustrated fourth edition of 1688, Paradise Lost had demonstrated its capacity to speak to divergent audiences. Milton’s unorthodox sacred epic, written by a blind and visionary radical Protestant poet, was now bestowed with the cultural authority of an English classic that rivaled its ancient models.

This illustration of the temptation of Adam and Eve, by John Baptist Medina (1659–1710), goes with Book IX in the first illustrated version of Paradise Lost, the 1688 edition. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

My lecture will emphasize the originality of Paradise Lost in two senses: its highly experimental revision of the epic genre, whose martial, imperial, and aristocratic values it subverts; and its exploration of our human origins in its depiction of the domestic life of Adam and Eve.

By placing Adam and Eve at the center of Paradise Lost, Milton gives the epic a much more domestic focus. Going well beyond the terse details of the Bible, Paradise Lost dramatizes the extraordinary intimacy and tensions between them, the tragedy of their fall, and their struggles to recover their strained marriage—all related by Milton with great psychological and emotional nuance. The poem’s originality consequently owes much to its probing and realistic depiction of human intimacy, frailty, and perseverance.

Today, 350 years later, that originality still holds tremendous power.

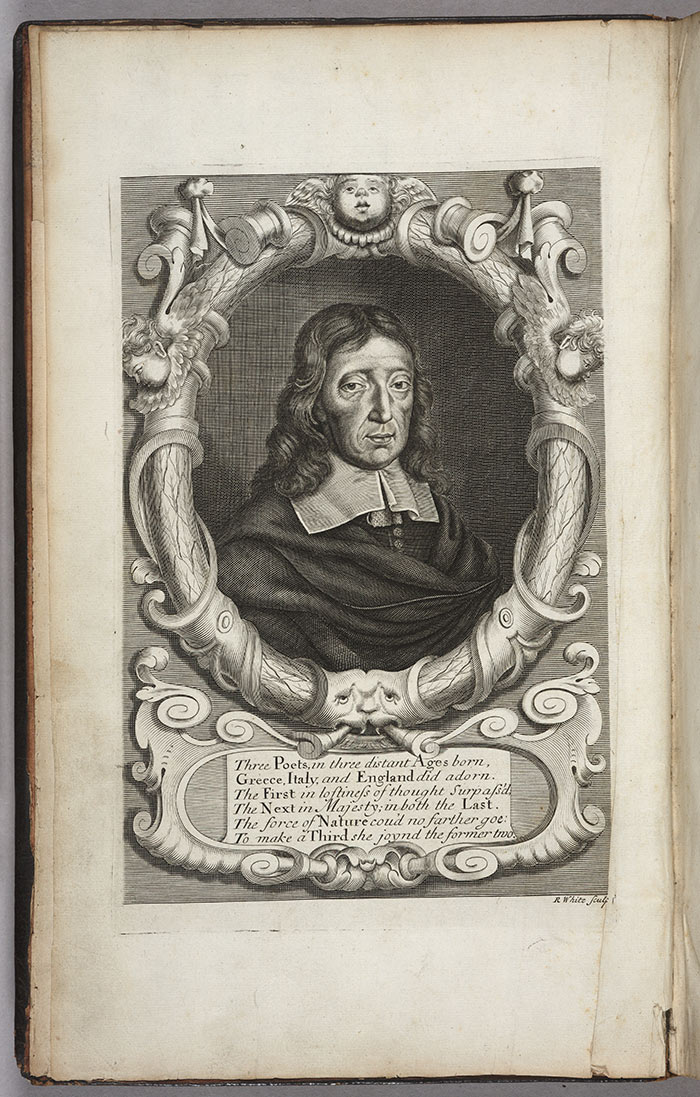

Illustration of the poet John Milton (1608–1674) in the frontispiece of the 1688 edition of Paradise Lost. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

You can see a copy of the first edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost in the permanent exhibition “Remarkable Works, Remarkable Times” in the Library Exhibition Hall.

You can listen to David Loewenstein's lecture on SoundCloud.

David Loewenstein’s Nov. 1 lecture, “The Originality of Milton’s 'Paradise Lost" will take place at 7:30 p.m. in Rothenberg Hall.

David Loewenstein is Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of English and the Humanities at Penn State. He is the editor of John Milton, Prose: Major Writings on Liberty, Politics, Religion, and Education (Wiley-Blackwell, 2013); author of Treacherous Faith: The Specter of Heresy in Early Modern English Literature and Culture (Oxford University Press, 2013); and co-editor of Shakespeare and Early Modern Religion (Cambridge University Press, 2015). He is also an Honored Scholar of The Milton Society of America.