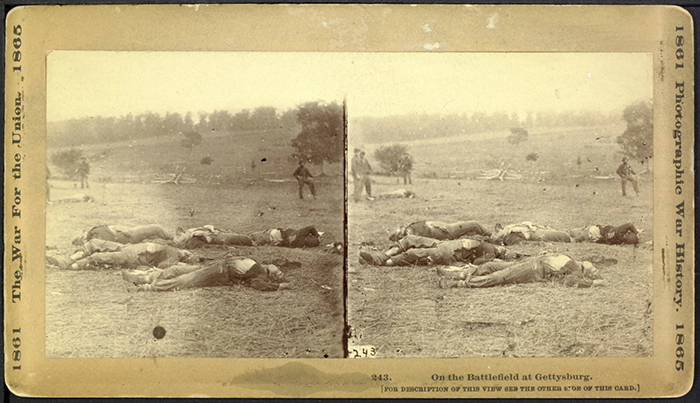

Photographs like Timothy H. O'Sullivan’s On the Battlefield of Gettysburg, showing bloated dead bodies, made war painfully real for many Americans. (1863, printed ca. 1891) The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

On Nov. 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln delivered one of the greatest speeches in American history: the Gettysburg Address. It was a delicate moment in the young nation’s identity. The Civil War had been raging for two years and the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1–3, 1863) had claimed 50,000 lives. For the first time, the country required a national cemetery. In dedicating the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Penn., Lincoln uttered his now famous words:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

Lincoln’s address continued for another minute or so, containing a total of ten sentences, a tiny snippet of dialogue compared to the main speech of the day, famed orator Edward Everett’s two-hour discourse. Yet in the ensuing months, years, and now decades, it would be Lincoln’s words, not Everett’s, which played over and over again in the minds of American schoolchildren, war veterans and others trying to make sense of the Great Conflict.

According to Civil War scholar David Blight, artist John B. Bachelder (1825–1894) walked every inch of the Gettysburg battlefield to render this map, showing roads, railroads, houses and places where officers were killed and wounded. (c. 1863) The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Today, more than 150 years later, America’s deadliest war continues to maintain a tenacious hold in our national conscience. Earlier this month, another president, Barack Obama, recalled the sacrifices so many made at Gettysburg when he posthumously bestowed the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest honor, on Civil War Union Army First Lieutenant Alonzo H. Cushing.

As Obama described, it was July 3, 1863, the third day of the battle, and Cushing had been wounded twice. With Confederate soldiers just 100 yards away in what is now known as Pickett’s Charge, Cushing refused to abandon his position, continuing to give orders to his battalion, saying he’d “fight it out, or die in the attempt.” Moments later, his attempt ended. He was 22.

On this day 151 years ago, Lincoln showed an uncanny sense for which words would best soothe a rattled nation. But in one crucial aspect, his remarks missed the mark. Lincoln predicted: “The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here.”

On the contrary, we remember Lincoln’s words — so eloquently stated, so long ago.

Implements of Modern Warfare (1875) shows one man’s fascination with Civil War objects. L.M. Buehler collected these items at the close of the war and made them into a curiosity cabinet that official Gettysburg photographer William H. Tipton called “the only one in the world.” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In recognition of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, The Huntington has held a number of commemorative events, including exhibitions, conferences, and lectures.

In 2012, The Huntington held a photography exhibition, “A Strange and Fearful Interest: Death, Mourning, and Memory in the American Civil War” and a concurrent Library exhibition, “A Just Cause: Voices of the American Civil War.” You can still visit the website of “A Strange and Fearful Interest,” which includes many of these images as well as commentary by historians such as Gary Gallagher, Joan Waugh, and David Blight.

Talks from “Civil War Lives,” a 2011 conference that brought together some of the nation’s most renowned Civil War scholars for a two-day event, can be found on iTunes U.

In addition, many lectures exploring themes relating to the Civil War are available in a special page on iTunes U, “Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War.”

Diana W. Thompson is a freelance writer based in South Pasadena, Calif., and a regular contributor to Huntington Frontiers magazine.