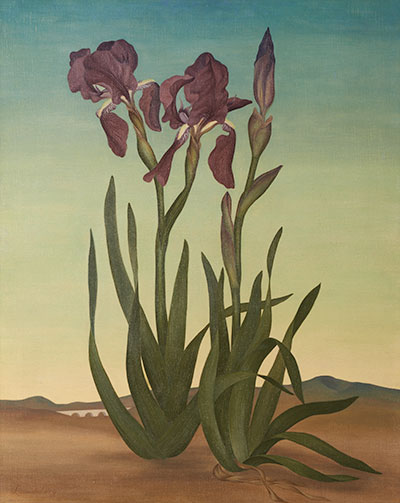

Left: Helen Lundeberg (1908–1999), Irises (The Sentinels), 1936, oil on canvas, 30 x 25 in. (76.2 x 63.5 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from the Art Collectors' Council, the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation Acquisition Fund for American Art, the Connie Perkins Endowment, Eleanor and Max Baril, Nancy Berman and Alan Bloch, Maribeth and Hal Borthwick, Caron and Steven Broidy, Jeri and Tom Mitchell, Margaret Richards, Susan W. and Carl W. Robertson, Ann and Robert Ronus, Laura and R. Carlton Seaver, Amanda Shore, Tim and Lisa Sloan, and Geneva and Charles Thornton. © The Feitelson / Lundeberg Art Foundation.

Left: Helen Lundeberg (1908–1999), Irises (The Sentinels), 1936, oil on canvas, 30 x 25 in. (76.2 x 63.5 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from the Art Collectors' Council, the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation Acquisition Fund for American Art, the Connie Perkins Endowment, Eleanor and Max Baril, Nancy Berman and Alan Bloch, Maribeth and Hal Borthwick, Caron and Steven Broidy, Jeri and Tom Mitchell, Margaret Richards, Susan W. and Carl W. Robertson, Ann and Robert Ronus, Laura and R. Carlton Seaver, Amanda Shore, Tim and Lisa Sloan, and Geneva and Charles Thornton. © The Feitelson / Lundeberg Art Foundation.

Don't expect a garden variety flower from a modernist painter

A rose is a rose is a rose, but what a rose can mean in different contexts is staggeringly varied. Take the red rose. A token of romantic affection, it is also the flower of the City of Pasadena and its world-famous Rose Parade. The British Labour party has taken it up as a logo, as has the Socialist International. Farther afield, the flower was a part of official Soviet ceremonies, including the funeral of Joseph Stalin. Unbelievably, the red rose connects Pasadena's Colorado Boulevard and Moscow's Red Square.

It is probably not just the brilliant colors and concentric, interlocking forms of flowers that enticed such artists as Helen Lundeberg (1908–99), Henrietta Shore (1880–1963), and Agnes Pelton (1881–1961), whose paintings of irises, clivias, and passion flowers recently entered The Huntington's collection. Just as flowers attract bees, they attract meanings. Humans cannot resist transforming them into symbols, and for Lundeberg, Shore, and Pelton, flowers are foils, ways to further their very different artistic agendas.

With longtime partner and later husband Lorser Feitelson, an abstract painter, Helen Lundeberg was a figure of note in the Los Angeles art scene from the 1930s until her death in 1999. The Huntington's Irises (The Sentinels) dates from her breakout decade, the 1930s, when her artworks contained an assortment of flagellum-propelled, cell-like bodies, carnivorous plants, distant galaxies, planets, optical instruments, and self-portraits. A drawing of hers at The Huntington shows her in profile on the right, as if she were dreaming up a mindscape of branches and flowers.

Right: Helen Lundeberg (1908–1999), Three Generations, 1937, color pencil on paper, 15 x 11 1/2 in. (38.1 x 29.2 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation Acquisition Fund for American Art. © The Feitelson / Lundeberg Art Foundation.

Right: Helen Lundeberg (1908–1999), Three Generations, 1937, color pencil on paper, 15 x 11 1/2 in. (38.1 x 29.2 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation Acquisition Fund for American Art. © The Feitelson / Lundeberg Art Foundation.

At one level, Irises (The Sentinels) is an object lesson in observation. Care has been taken to render the vascular tissue of stems, the involutions of the petals, and their branching patterns of white and purple. At another level, the overall effect is disquieting—not what one expects of a floral illustration. Why? Irises often grow in semi-arid environments, but this imagined landscape resembles a hot desert climate, dry and devoid of plant life except for a greenish tint on the distant hills that might be groundcover. Besides their improbable ability to thrive, the irises appear to be eerily sentient. Their outstretched, tentacle-like leaves caress each other and brush against the ground. (Could they uproot themselves and sidle away, like an octopus escaping an aquarium?) They stand upright, and their stems, like twisted necks, crane, as if to take in something in the distance. Alone in the desert, they are, indeed, sentinels keeping watch over a place where they do not belong.

During the 1930s, Lundeberg's career rode the wave of French Surrealism that had arrived recently in the United States. In 1936, she was included in the epochal Museum of Modern Art exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism, organized by its famed director and indefatigable promoter of modernism, Alfred H. Barr Jr. Nonetheless, she had made an effort to establish distance from surrealism. In an October 1934 artist's statement, she declared her work to be "New Classicism," which she called a "Post Surrealist movement." This was possibly the first avant-garde manifesto written in Southern California. She provides a clearer explanation of Post Surrealism in a statement in a 1942 Museum of Modern Art catalog: "The pictorial elements [subject matter] are deliberately arranged to stimulate, in the mind of the spectator, an ordered, pleasurable, introspective activity." Put another way, the various objects she includes are arrayed to provoke thought. For example, those healthy irises in the bone-dry desert do not make any sense, and their juxtaposition may trigger an internal self-critical awareness. While the Parisian Surrealists wanted to disorient, the Post Surrealist Lundeberg tugs and slightly confuses, like a pleasant dream with a nagging something-does-not-add-up feeling.

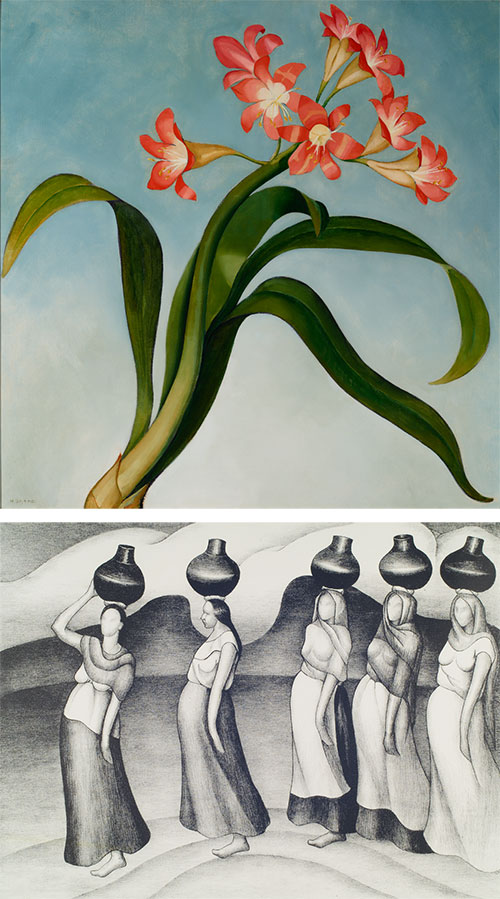

Left (top): Henrietta Shore (1880–1963), Clivia, ca. 1930, oil and pencil on canvas laid down on board, 26 x 26 in. (66 x 66 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation Acquisition Fund for American Art. © Estate of Henrietta Shore Left (bottom): Henrietta Shore (1880–1963), Women of Oaxaca, ca. 1929, lithograph, 14 x 18 1/2 in. (35.6 x 47 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of Hannah S. Kully. © Estate of Henrietta Shore

Left (top): Henrietta Shore (1880–1963), Clivia, ca. 1930, oil and pencil on canvas laid down on board, 26 x 26 in. (66 x 66 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation Acquisition Fund for American Art. © Estate of Henrietta Shore Left (bottom): Henrietta Shore (1880–1963), Women of Oaxaca, ca. 1929, lithograph, 14 x 18 1/2 in. (35.6 x 47 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of Hannah S. Kully. © Estate of Henrietta Shore

Henrietta Shore hailed from Toronto, Canada, and later shuttled between New York City and Los Angeles before settling in Carmel, California. She was never very productive, and a relatively small body of work survives. Moreover, late in life, she was committed to an asylum in San Jose, where she died in 1963. She had no children, and there was no firm evidence of romantic attachments, though she and the photographer Edward Weston, who also lived in Carmel, had a close, if at times fractious, friendship. Yet for all the obscurity she fell into during the last decades of her life, she had once been lauded as a rising star. In 1927, a reviewer in the Christian Science Monitor said "she is unquestionably one of the most important living painters in the United States."

Shore's Clivia was likely painted in the late 1920s or 1930s, when she was most productive and had befriended Weston. Clivia lacks the unsettling quality of Irises or the hallucinatory glow of Pelton's Passion Flower, but it shares their placelessness. None of these paintings of flowers are located in the complicated ecosystems that sustain life. The viewpoint of Clivia is tilted and skyward, which crops out any hint of soil or even the pot that it might be growing in. Centered on the canvas, the clivia plant obediently splays its leaves and salmon flowers just up to the frame, too pleasing to be observed from life. The flowers have a cold beauty, more like hammered sheets of metal than soft petals. Shore drew a pattern of crisp outlines in pencil, then filled them in with precisely applied oil paint that resembles baked enamel. The dark substructure of lines comes through here and there as if the plant were assembled from die-cut parts—making it look more like a brightly colored machine than a pliant, living thing. In Clivia, it is as if the artist had distilled the floppy parts of actual, living plants into hard, idealized forms, like mathematical diagrams that describe underlying structure. This is not the picture of a single plant, but the sum of her observations of many. Her flowers are neither artificial nor exactly possessing the quality of being alive. One critic's remark about Shore's work could aptly be applied to the piece. Reginald Poland, the first director of what is now known as the San Diego Museum of Art, described her art as aimed "toward the greater goal of a vital, impelling creation that is not merely life but more than that, an intensification of life."

Without being a biologist or mathematician, Shore, through her art, nonetheless grasps at the structures, the sinusoidal curves, Fibonacci sequences, and branching patterns that are the scaffolding on which all lifeforms depend. Her simplifications are an unveiling of the order inherent to life-forms.

While Helen Lundeberg co-opted the iris for her Post Surrealist agenda and Henrietta Shore pared down the clivia to an essential pattern, Agnes Pelton gives us a luminescent and hallucinatory passion flower vine. In Pelton's hands, this vine is untethered from any support and emerges from a glowing violet background. Leaves, buds, tendrils, and an open flower do not connect to each other; instead, they appear to float in a liquid solution. The central flower expands, an aureole of light with rays formed by alternating green and pink petals. Light within the painting is peculiar and without a definite source; the red shadows on the green tendrils and the spectral highlights along the leaves' edges suggest multi-colored lights from multiple sources. (Or, perhaps, the plant is bioluminescent, glowing like a deep-sea creature?) In Pelton's painting, the passion flower's bloom is painted with a controlled impasto. This embossed texture sits above the rest of painting's surface and makes it seem as though the flower is about to break out of the fantastic space inside the painting into the real space of the spectator. While Passion Flower is representational, Pelton listed it among her abstractions, many of which were captioned with poems. About The Huntington's painting, she wrote: "Blooming intensity, center of light."

Right: Agnes Pelton (1881–1961), Passion Flower, ca. 1945, oil on canvas, 24 x 16 in. (61 x 40.6 cm). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Purchased with funds from the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation Acquisition Fund for American Art.

The otherworldly quality of Passion Flower is typical of Pelton's abstractions, though many of the others contain pulsations of light, cloud-like forms, and energetic patterns. Her turn to abstraction came in 1925 and was based on her reading of mystics and theosophists. Like many early 20th-century artists, including Vassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian, Pelton believed that visual art could reach into a spiritual realm and that visual forms were capable of speaking directly to a viewer, bypassing the limitations of everyday language to communicate a message about the oneness of the universe. In 1929, she penned an artist's statement that leans on the flower as a metaphor for her aesthetic goals: "As the fragrance of a flower fills consciousness with the essence of life without the necessity for seeing its material form, it seems that color will someday speak directly to us...carrying a more direct impact on our newly developing perceptions." She wanted to make paintings with the sensory intensity and immediacy of smell to launch viewers onto a higher plane. Like many of her contemporaries, her synesthetic conflation of smell and sight was stimulated by Kandinsky's 1912 book Concerning the Spiritual in Art. She also compared color arrangements to musical harmonies. In her sketchbooks, she placed color symbols on musical staves, as if writing a song in which each color formed a note.

Pelton came from a musical family, so equating colors with music had a homegrown aspect. Born in Germany, she moved to Brooklyn as a child with her mother, who for 30 years ran the Pelton School of Music. She studied piano at home and art at Pratt Institute. Pelton later lived in bohemian Greenwich Village and exhibited at the Armory Show of 1913, which introduced a skeptical American public to modernist art. In the 1910s and 1920s, she visited Italy, Lebanon, Hawaii, New Mexico, and California. In 1932, she settled in Cathedral City, California, only a few miles from the resort area of Palm Springs, where she remained for the rest of her life and eked out a living by selling desert landscapes to tourists. She exhibited regularly through the 1940s and was the honorary president of the Transcendental Painting Group, which was founded in Taos, New Mexico, in 1938. The group's members believed, as she did, that abstract art could transport people to hitherto unknown levels of reality.

Today's art world is more often associated with commerce and materiality—with a daily parade of headlines reporting record prices for works sold at auction—than with utopian consciousness raising or, as artists in Pelton's day sometimes called it, a fourth dimension of reality beyond what we can see. With her spiritualist views and belief in abstraction's ability to capture them, Pelton turns a delicate passion flower into a logo for evangelical modern art. Lundeberg and Shore are less fervent, but they still take up flowers as vehicles for their artistic purposes. Lundeberg's purple irises are gently unsettling Post Surrealist signs, and Shore articulates the architecture of the clivia's stems, leaves, and flowers as if it could be broken into components and reassembled. Like the Soviets and the Pasadena Rose Parade organizers, who co-opt the red rose to vastly different ends, these artists use flowers as beautiful messengers to deliver their ideas.

James Glisson is the Bradford and Christine Mishler Associate Curator of American Art at The Huntington.