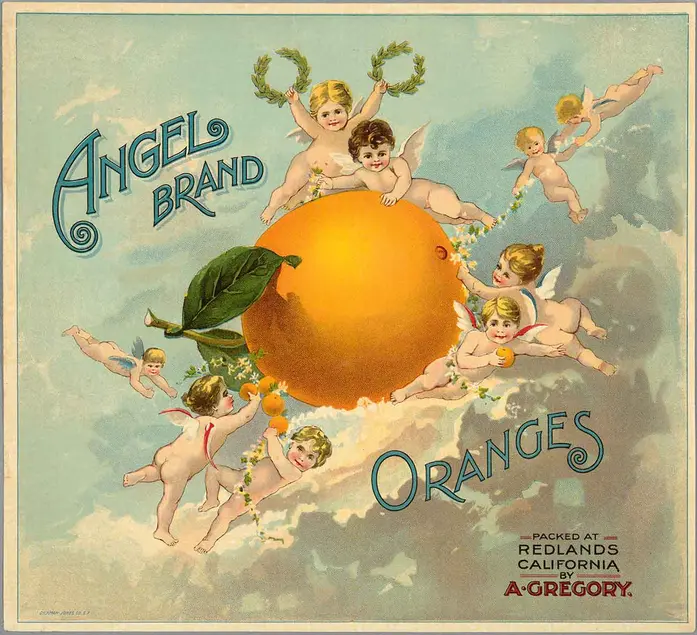

Spirit Boys: Putti and Infant Gods on Paper

As you explore The Huntington's galleries and gardens you will encounter those familiar little figures: playful young boys who feature frequently in works of art. Whether carved in stone or painted on canvas, they are so common that we take them for granted. But what exactly are they?