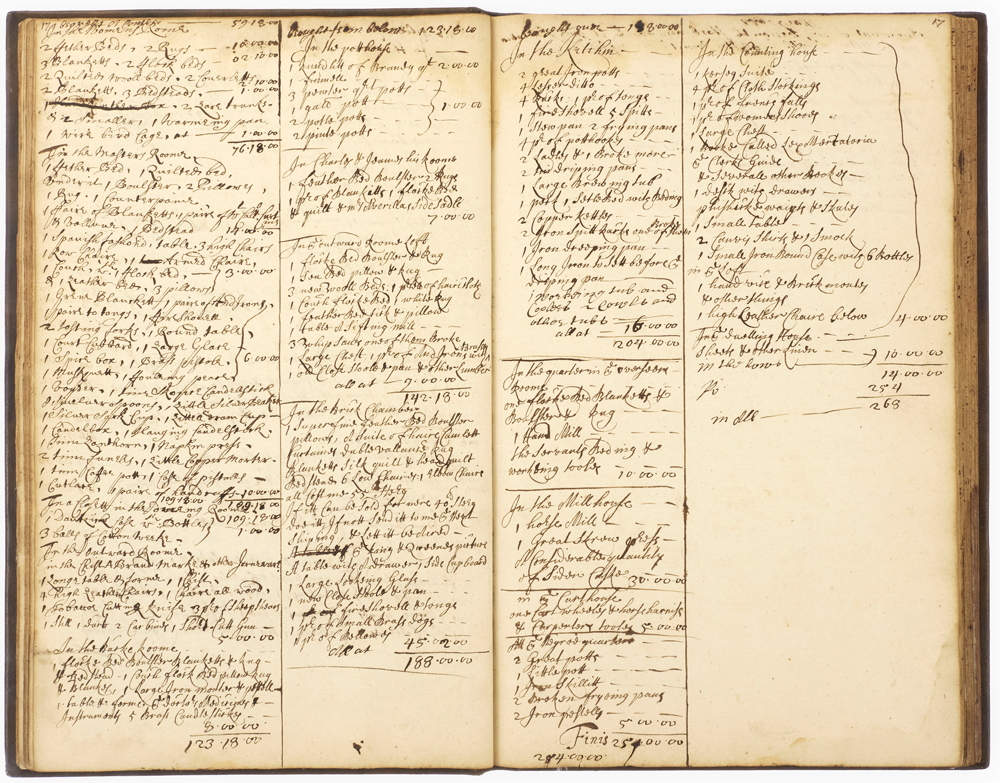

An unpublished and unstudied early modern manuscript account book and ledger of plantations in Virginia owned by the English merchant and banker Robert Bristow (1634–1707). The book contains 94 folios in a variety of hands, including Bristow’s own. The volume includes accounts, ledgers, surveys of plantations, inventories of dwelling houses and stores, copies of land patents and other legal documents, and lists of indentured and enslaved laborers. The manuscript spans the years 1677 to 1707. | Photo courtesy of Bernard Quaritch Ltd.

The Huntington has acquired six extraordinary collections through the generosity of the Library Collectors’ Council, a group of supporters who help fund the purchase of new items to add to the Library’s holdings.

This year’s acquisitions include the 17th-century account book of an English owner of plantations in colonial Virginia; letters by Florence Nightingale (1820–1910), one of the most influential figures in the history of modern nursing; 216 images by European photographers depicting changes in the Philippines from 1858 to 1910; the papers of the Hudson Valley’s Duryea family, a collection spanning from the colonial era to after the Civil War; an illustrated 19th-century natural history of pine trees; and a 19th-century book of original poems and hymns written by Thomas Young, a self-taught Black author.

“The Library Collectors’ Council convenes annually to hear our curators bring to life the voices of other times and places—voices that are embodied in books, letters, photos, and ephemera,” said Sandra Brooke Gordon, Avery Director of the Library. “Over the years, through their collective wisdom, the Council has selected scores of these voices to make a permanent home at The Huntington. We are grateful for their generosity, discernment, and friendship.”

Founded in 1998, the Council met for the 27th time last month. Highlights of the acquisitions include:

Detail of Robert Bristow’s account book and ledger of plantations in Virginia. | Photo courtesy of Bernard Quaritch Ltd.

An Account Book of an Englishman in 17th-Century Virginia

Robert Bristow (1634–1707) was a prosperous London merchant until 1660, when he traveled across the Atlantic, just 53 years after the settlement of the colony at Jamestown. Bristow was after fortune. He and his wife, Averilla Curtis, established a plantation in Gloucester County, Virginia, an enterprise that grew over the next four decades to include several other plantations (totaling more than 2,500 acres) around the Chesapeake. Bristow’s account book captures in granular detail how his family spent their English money building American plantations.

“No detail is too small for inclusion in this volume,” said Vanessa Wilkie, William A. Moffett Senior Curator of Medieval Manuscripts and British History and head of Library Curatorial. “For example, the manuscript contains a 10-page inventory of home goods, bullets, and even books that comprised Bristow’s personal home library. What is even more powerful is that these notes are written alongside inventories of human chattel.”

When Bristow first began operating his farm on land originally controlled by part of the Powhatan Confederacy, he relied on indentured servants from Britain. This manuscript documents, over the course of time, the decline of indentured servants and the rise of enslaved Africans on Bristow’s lands.

“These details offer unique historical evidence for how the British Atlantic slave trade developed into the American plantation system. It isn’t enough to know that slavery happened; we need to understand why and how it happened,” Wilkie said.

In 1676, Bristow joined pro-English militias in opposition to Bacon’s Rebellion, and he was ultimately captured by rebels who raided his plantations. After his release, Bristow returned to England, but he appointed an estate manager to continue running his Virginia plantations. The manager maintained Bristow’s account book for nearly another 30 years, while Bristow used his growing American-generated wealth to advance his investments in England.

In the 1690s, Bristow became master of the Grocers’ Company and ultimately a director in the Royal African Company, one of the major slave trading companies of the age. The Bristow volume accounts for all of this, but its contents are magnified when considered within the context of one of The Huntington’s most significant holdings: one of the world’s largest and most important archives for the Royal African Company, a part of the iconic Stowe Collection, which Henry E. Huntington acquired in 1925.

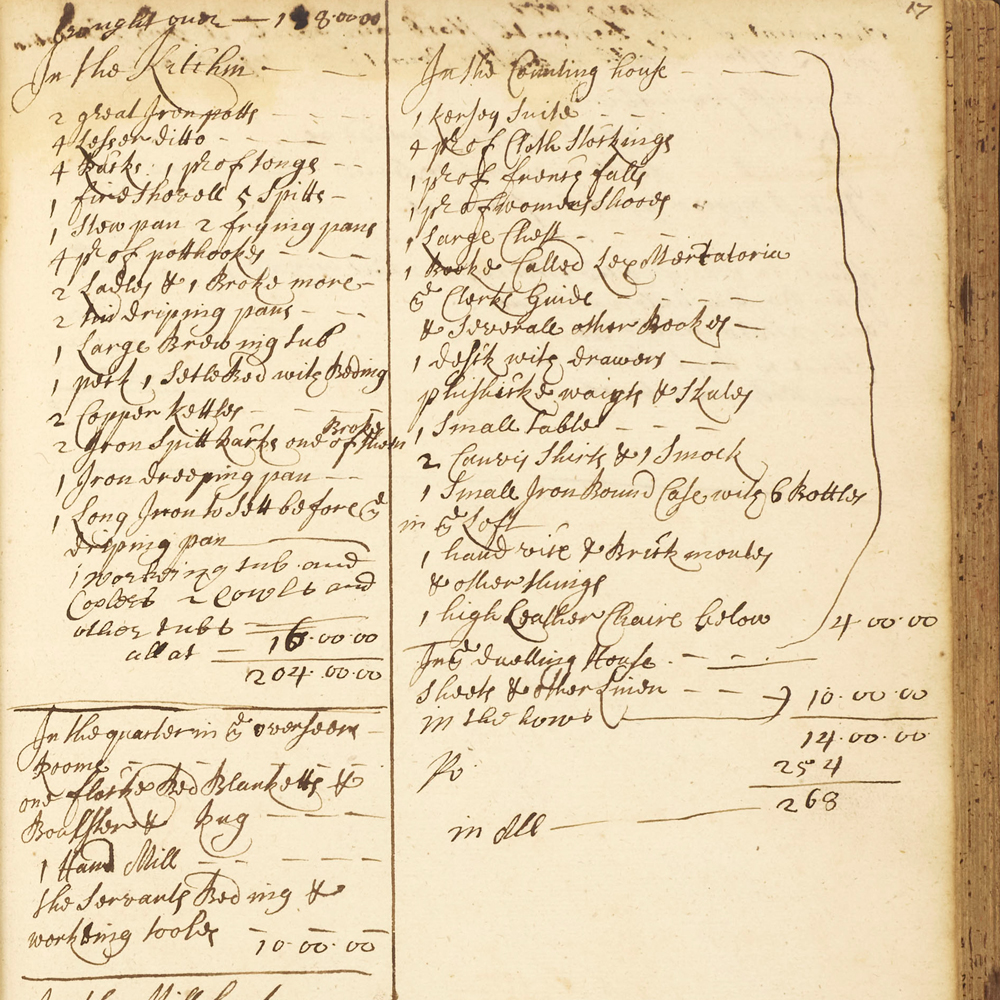

Florence Nightingale letters, exchanged from 1883 to 1896, 16 letters that amount to 74 pages. 11 signed autograph letters; 1 autograph letter; 1 signed autograph correspondence card; 2 letters (one signed); and a signed facsimile autograph letter. | The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Florence Nightingale Letters: Pioneering Insights into Nursing and Social Reform

“This compilation of manuscript correspondence, dating from 1883 to 1896, features a unique assortment of personal writings by Florence Nightingale, offering major insights into her exceptional contributions to nursing and her efforts for social and professional reform during a pivotal era in British history,” said Joel Klein, Molina Curator for the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences.

Nightingale is largely remembered for her groundbreaking use of statistics to analyze health outcomes in hospitals. This innovative approach shed light on the paramount importance of methodically collected data in medical decision-making, establishing part of the foundation of evidence-based medicine. During the Crimean War, Nightingale spearheaded revolutionary changes in military health care by implementing novel nursing practices that substantially enhanced sanitary conditions in war hospitals.

Nightingale’s primary correspondent in the letters was Jessie Lennox (1830–1933), a close friend who was among the original “Nightingale Nurses” trained at St. Thomas’ Hospital School of Nursing in London. Within the exchange lies not only a historical narrative documenting the evolution of nursing but also a manifestation of Nightingale’s unwavering vision: the elevation of nursing as an autonomous profession deserving respect on its own merits.

The collection displays Nightingale’s bold and forward-thinking ideas, including her holistic approach to health and welfare, which emerges in a discussion of her attempts to improve conditions for underprivileged children in an industrial home. In addition, her letters show how she navigated a predominantly male professional world, as reflected in her frustration: “This … is a difficulty because the man-Committee does not seem to think a woman has any business in the Barrack huts at all.”

The collection has noteworthy relevance to The Huntington’s holdings on medical history, especially those on women and medicine, complementing, for example, the Lawrence D. and Betty Jeanne Longo Collection in Reproductive Biology. It also aligns well with The Huntington’s holdings on Elizabeth Blackwell (1821–1910), the first American woman to receive a medical degree; the holdings include one of Blackwell’s manuscript notebooks and more than 100 books from her personal library. Additionally, the Nightingale collection augments The Huntington’s resources on nursing during wartime, which include important collections from numerous conflicts on both sides of the Atlantic.

Unknown photographer, Group of women reading La Independencia newspaper, ca. 1898, albumen print. | The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Visions of the Philippines: A Rare Collection of 19th-Century Photography

“This extraordinary group of photographs consists of vivid scenes and portraits taken in the Philippines during the late 19th century,” said Linde B. Lehtinen, Philip D. Nathanson Curator of Photography.

The collection, assembled over a period of 35 years by Serge Kakou, includes an album with extensive views of Manila and surrounding areas; stereographs of village life by German ethnographer Fedor Jagor; stereographs documenting damage from the 1863 Manila earthquake; stunning studio portraits and architectural photographs by Europeans based in Manila, including Albert Honiss and Francisco van Camp; and multiple shots of people and local landscapes.

Subjects range from city streets and shops, monuments, churches, and bridges to lush countryside, Indigenous tribes, family gatherings, religious customs, agricultural workers, and the aftermath of natural disasters. Each image conveys important information about the political, economic, and cultural climate of the Philippines during a time when its long colonial history with Spain was about to shift. After its defeat in the Spanish-American War of 1898, Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States. This was followed by the Philippine-American War, lasting from 1899 to 1902, between American forces and Filipino nationalists who sought independence rather than a change in foreign power.

“These early photographs reveal intersecting stories of community, heritage, destruction, progress, exchange, and resilience that make for a remarkable visual representation of Asian life and identity,” Lehtinen said.

Photography first appeared in the Philippines in the 1840s, shortly after the announcement of its invention in 1839 in France. Sinibaldo de Mas, a Spanish diplomat in Asia, is often credited with bringing this new technology to the area. By the 1860s, the use of photography in the region became widespread and the first known photographic studio was established by British photographer Albert Honiss in 1865. When Honiss died in 1874, Dutch photographer Francisco van Camp took over his business. The work of Honiss and van Camp is a significant part of the collection, presenting important examples of the earliest activities of commercial photography studios in the Philippines.

Other notable photographs include a group of women reading La Independencia, the periodical organ of the Philippine Revolution against Spain led by Emilio Aguinaldo, whose papers reside at The Huntington. There are also substantial sets of stereographs: One series of the 1863 Manila earthquake depicts rare urban views of this period, and another by Fedor Jagor features individuals from the Tinguian ethnic group—some of the earliest known portraits of Indigenous peoples in the Philippines.

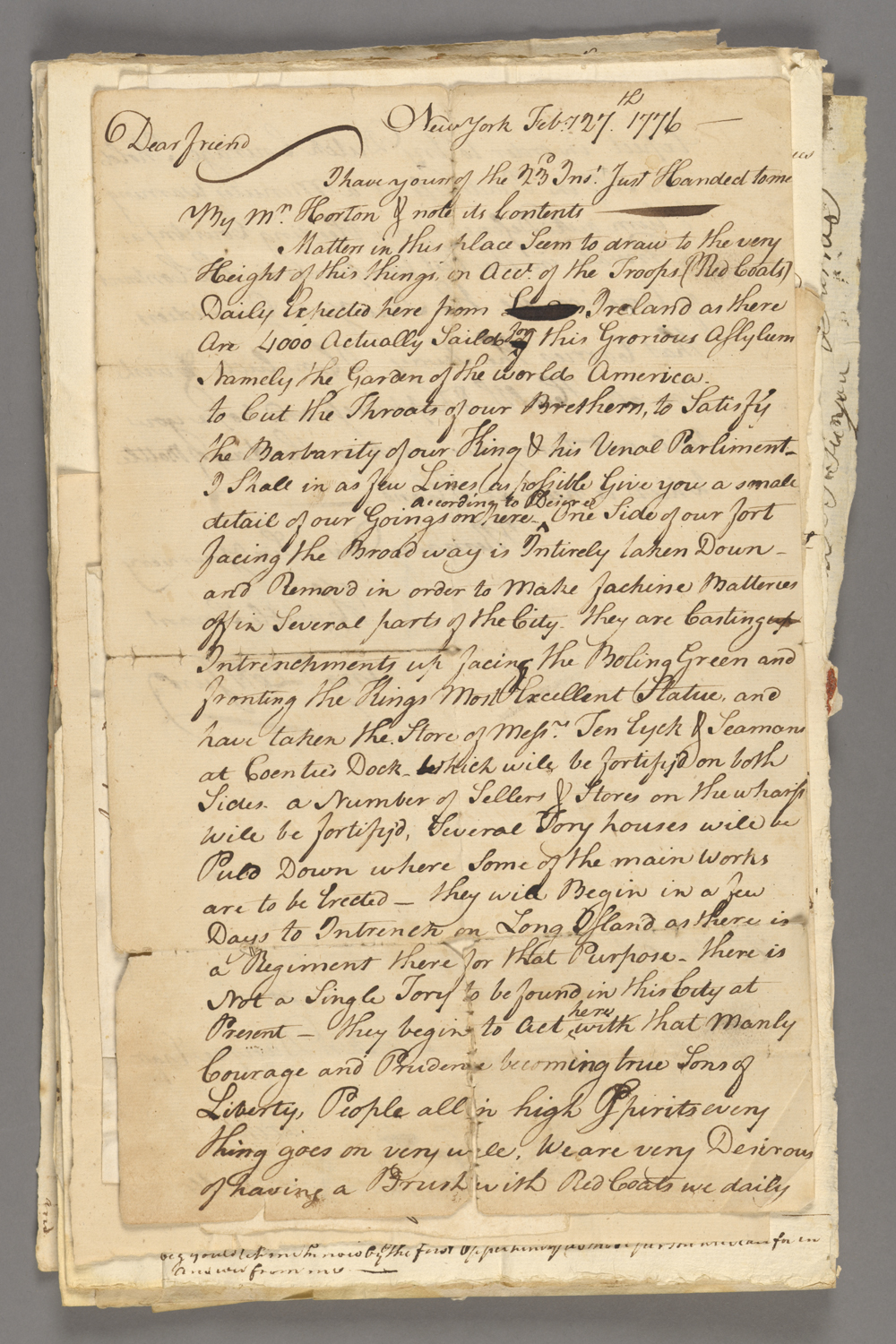

Engelbert Lott to Stephen Duryea, Feb. 27, 1776, from the archive of the Duryea family of Fishkill, New York. The archive contains more than 700 letters, 31 manuscript volumes, and approximately 1,000 pieces of miscellaneous writings and ephemera, 1760–1920, bulk 1768–1865. | The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Archive of the Duryea Family of Fishkill: A Century of New York History

On Feb. 27, 1776, New York merchant Engelbert Lott sat down to write a letter. The city was abuzz with the news of some 4,000 “Red Coats” who had already sailed from Ireland “for this Glorious Asylum namely the Garden of the World America,” intent to “Cut the Throats of our Brethren to Satisfy the Barbarity of our King & his Venal Parliament.” The city was preparing for war: There were houses being “pull’d Down” to give way to fortifications. Lott proudly reported that he was holding himself “in Readiness at a Minute’s warning to turn out in Defense of our bleeding Country.”

Lott was writing to his friend and business partner, Stephen Duryea (1744–1776), scion of an old, well-connected New York Dutch family. A few months later, Lott would be taken prisoner by the British, and Duryea would die of disease contracted during military service on the side of the Patriots.

This letter is but a small part of this remarkable collection of papers accumulated by Stephen and his older brother Abraham (1742–1802). The Duryeas, well-off and well-connected merchants, were also slaveholders. Their papers—and especially their account books—contain a trove of information on the lives of Black New Yorkers in the late colonial and Revolutionary eras. The first federal census in 1790 counted more than 21,000 enslaved New Yorkers, nearly as many as in Georgia.

“This previously unseen collection is a fitting addition to The Huntington’s holdings on the political, social, economic, gender, and religious history of New York,” said Olga Tsapina, Norris Foundation Curator of American History. “It covers an extraordinarily broad range of subjects, from the colonial era to the Civil War and beyond. Its content on the history of enslaved people makes it exceptional.”

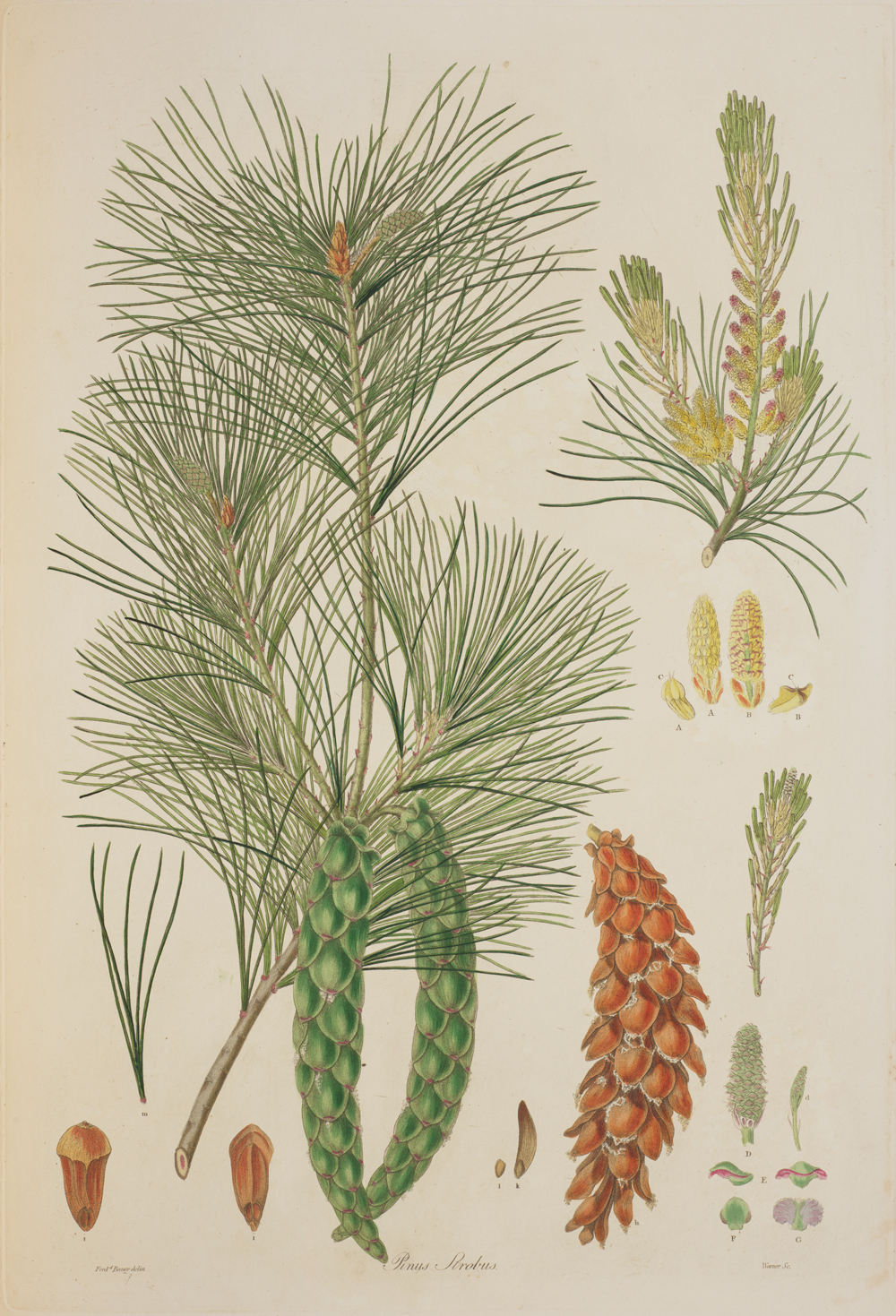

Pinus strobus (Eastern white pine), details of fascicles and cones, plate 28 in Aylmer Bourke Lambert’s A Description of the Genus Pinus, with Directions Relative to the Cultivation, and Remarks on the Uses of the Several Species …, London: James Bohn, 1842. With a total of 97 hand-colored engraved plates. | The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

A Natural History of Pine Trees

“British botanist Aylmer Bourke Lambert was a busy man,” said Daniel Lewis, Dibner Senior Curator for the History of Science and Technology. “Along with his collection of 50,000 plant specimens, he tended to his biggest obsession: pine trees and their varieties and distinctions—details he longed to make available to a wider world.”

Lambert’s book A Description of the Genus Pinus brings together for the first time knowledge about pine trees. His work involved close comparison of species and correspondence with a far-flung network of tree experts, including his friend and colleague Joseph Banks (1743–1820), a renowned British naturalist and president of the Royal Society.

Lambert’s long work was a complex, ongoing production, and its development tracks the changing understandings of pine trees. First published in 1803, with only a few plates, Lambert’s book expanded steadily, appearing in various formats over the next several decades. The Huntington’s copy, however, is the first edition to gather all the plates into a single, large-format volume—and, in fact, it is the final product of this decadeslong printing and publishing undertaking. The majority of the plates are by Ferdinand Bauer, an Austrian botanical illustrator of great skill who worked closely with Lambert, channeling the British botanist’s deep knowledge of trees.

Lambert’s work left a deep mark on artists and naturalists across continental Europe. German writer Johann Goethe, late in his life, was “deeply impressed” by the splendid illustrations in the volume. As one writer noted, with the arrival of Lambert’s book, “the botanical draughtsman was no longer the mere recorder of floral beauty, but now had the more difficult task of serving both Art and Science.”

“This historic record of pine trees provides essential groundwork for our understanding of the living, breathing tree,” Lewis said. “The Huntington’s own pine trees thrive on the grounds today—from hundred-foot-tall coast redwoods to bonsai pines. Old but mighty in their own ways, these living trees are the embodiment of Lambert’s work.”

Thomas Young, Afro-American Freeman’s Light. Denver: H. D. Mann & Co., Music Printers, 1896. | The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

A Rare Book of Original Hymns and Poems by an African American Author in Colorado

“This ambitious work offers a window into popular religious expression, musical print culture, and African American literary traditions,” said Josh Garrett-Davis, H. Russell Smith Foundation Curator of Western American History.

Thomas Young published his book Afro-American Freeman’s Light: A Book of Original Poems and Songs in 1896, as a resident of Colorado Springs. It is a small, very rare book comprising three original poems, 50 original hymns, and a short autobiographical account from Young. Only five copies appear in American libraries, none of them west of the Mississippi River. Published by Denver’s H. D. Mann & Co., who advertised itself as “Job & Book Printers” offering “First-class Work at Reasonable Prices,” the book is a truly remarkable example of a self-taught Black author who made his mark on local print culture in a Western city, seeking to become a “man of note.”

Young was born in 1860 in Batesville, Mississippi, to a formerly enslaved mother of four. His father died when he was very young. Young attended only about one cumulative year of school in his youth, but as an adult he diligently taught himself to read and write after days of hard labor. He also served many roles at Methodist Episcopal churches, ranging from singer to Sunday school participant to “exhorter.” He moved west to the Mississippi Valley, then farther west in 1892 to Colorado Springs, where he worked as a manager in the servants’ hall at the Antlers Hotel.

The Antlers was Colorado Springs’ largest employer of Black men, who worked as dining staff and bellhops, among other positions. In his spare time, Young composed the many works in Afro-American Freeman’s Light.

“The book will be a resource for researchers studying African American literature, music, and print cultures, Methodist Episcopal Church history, and publishing in the American West,” said Garrett-Davis. “It can also serve as a resource for community members, musicians, and others who wish to bring the past to life through performing historic music.”

The book was acquired with additional funds from Library Collectors’ Council members who stepped up to make the purchase possible.

Kevin Durkin is the managing editor in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington.