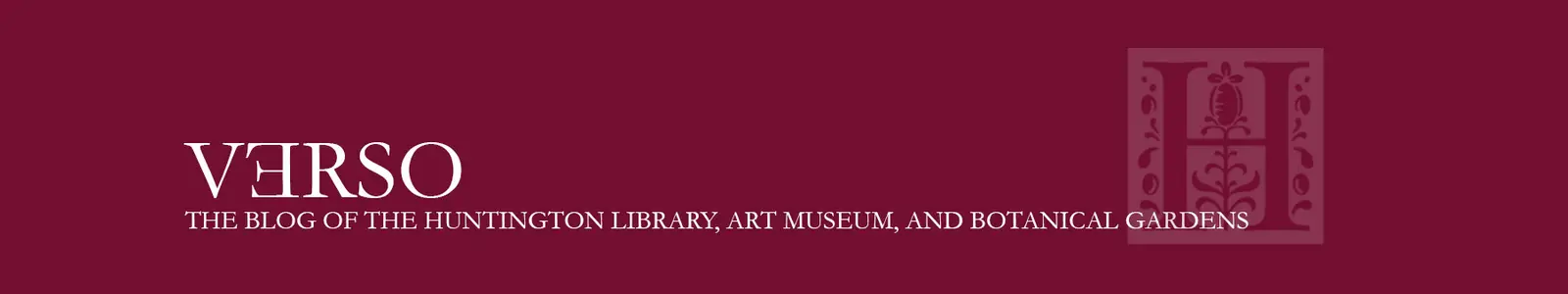

Petrarch shot by Cupid’s arrow at first sight of Laura, French edition of Petrarch’s poetry (RB 144265), 1564, page 17. | The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The first bestseller in the history of Western print was a love story. Petrarch’s poems about his adoration of a woman named Laura made the couple the most famous of the Renaissance.

Petrarch wrote that he first saw Laura at a church in the French city of Avignon on Good Friday, April 6, 1327. The observance of Christ’s crucifixion might seem an unlikely occasion for love at first sight, but Petrarch goes all in with his poem on the event, likening the darkness that befell the Earth during the crucifixion to his being blinded by love.

Petrarch didn’t invent the sonnet, but he did revolutionize it—a literary feat that still impacts how we talk about love. Without Petrarch’s poems, Shakespeare never would have compared his beloved to a summer’s day; without Petrarch’s obsession with Laura’s veil, Taylor Swift never would have sung about Jake Gyllenhaal making off with her scarf.

Centuries before the pop song, love sonnets provided the thrill of peeking into another’s romantic experience. Petrarch’s verses provided the terminology for falling in love that we now think of as universal, like opposing sensations (ecstasy and despair) and obsession as ailment (“lovesickness”). We tend to think of poetry as private, like a diary written in rhyme, but Petrarch’s opening sonnet, pictured above in the original Italian, addresses an audience: Voi ch’ascoltate in rime sparse (You who listen in scattered rhymes).

When Laura died suddenly in 1348, Petrarch’s grief was immense: “This life holds no further pleasures for me,” he mourned in a private obituary for her on the flyleaf of a precious book in his personal library. In the woodcut above, Apollo, god of poetry, tries to honor Petrarch with the laurel crown, but the poet is too brokenhearted to care.

Petrarch turned his pain into writing, ultimately composing 366 poems for Laura. He was still working on them when he died in 1374. His handwritten collection is preserved in the Vatican Library.

Petrarch also wrote many significant works in Latin, and his devotion to the rebirth, or renaissance, of ancient culture made him famous as the first “Renaissance man.” But readers ultimately proved less interested in classical disputation than a juicy love story, and once the printing press made its way to Italy in the late 15th century, Petrarch and Laura’s love story took on a life of its own.

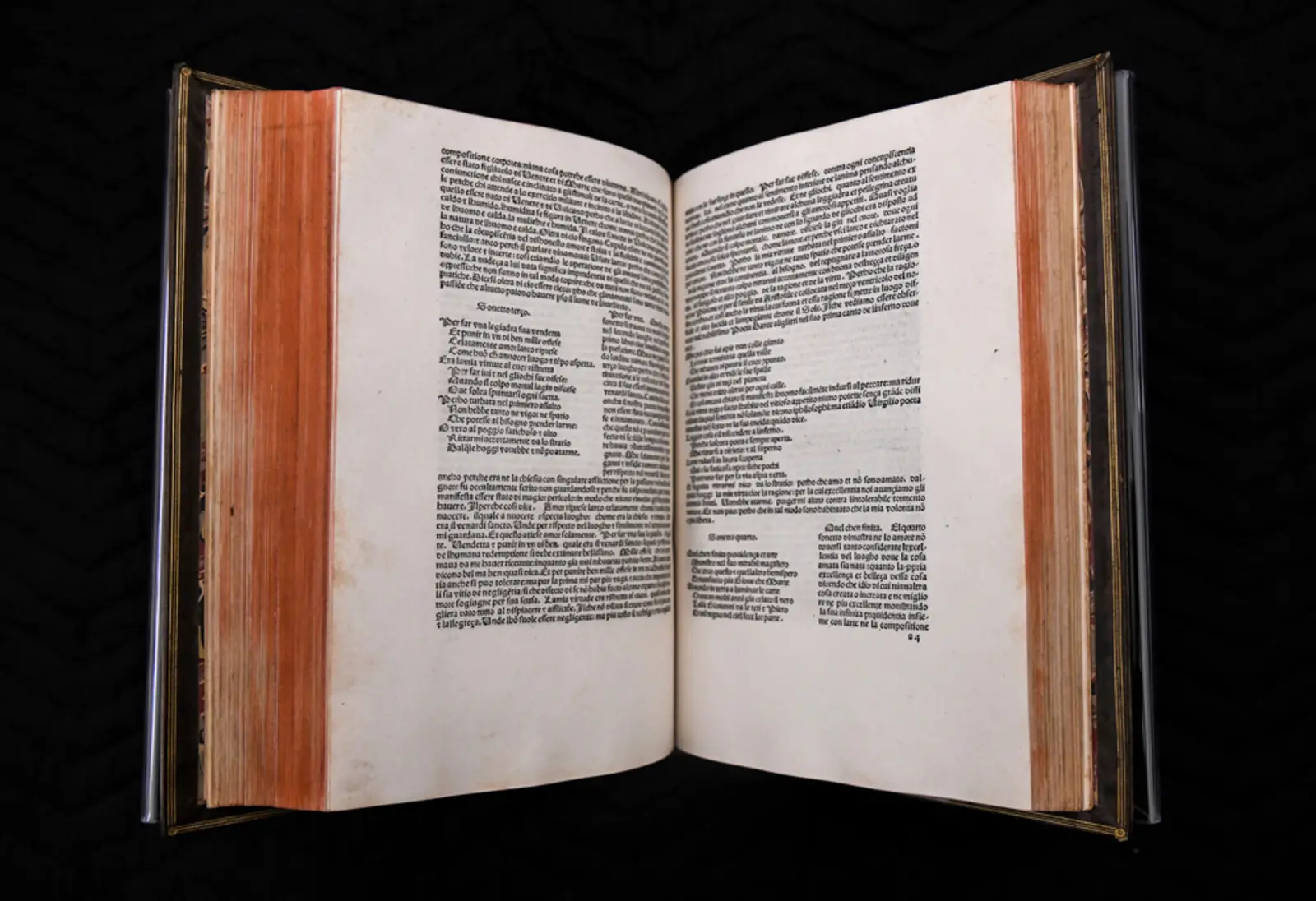

“Petrarch mania” swept the Renaissance reading public, an eagerness apparent in such objects as the map below, created by Alessandro Vellutello, who used the poems to retrace Petrarch’s and Laura’s steps.

For more information about Vellutello’s map, click the image’s hotspots. | Map of Petrarch and Laura’s environs, second edition of Alessandro Vellutello’s Petrarch (RB 357019), 1528, folios aa4v and aa5r. | The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

ORIENTE (East): The map is oriented with east at the top. This was a common feature of European maps until the early 16th century. Medieval Europeans tended to align geographic and religious axes, with Jerusalem at the center and the Garden of Eden to the east, in the direction of the sunrise and at the top of the map. Only during the Renaissance resurgence of the ancient cartographer Ptolemy would north become the default “up” direction on European maps. In the rendering of the map’s creator, Alessandro Vellutello, this arrangement has the added advantage of placing the two main locations of the Petrarchan narrative—the woods of Vaucluse and the city of Avignon—at the map’s center.

LE RONE (Rhône River): The Rhône is the major geographic feature signaling that the map is set in France. Petrarch was an Italian poet, born in 1304 in Arezzo, near Florence, in the region of Tuscany. He moved to Avignon as a child, when his father took the family there to seek work at the court of the exiled pope. He would move back and forth between France and Italy for the rest of his life. His poems were written in his native Italian—specifically, in the Tuscan dialect that he made famous alongside fellow writers Dante (1265–1321) and Boccaccio (1313–1375). Together, the writers are known as the tre corone, or “three crowns,” of Italian literature.

LA SORGA (Sorgue River): The whole of the Sorgue is captured within Vellutello’s map, from its source spring near Vaucluse at the top to where it joins the mightier Rhône at the bottom. The river is often featured in Petrarch’s love poetry. In the opening to sonnet 318, he calls Laura “she for whom I traded the Arno for the Sorgue,” referencing how proximity to her came to outweigh all else, even his desire to be in his beloved Florence and its own famous river. In poem 281, he describes how Laura’s ghost seems to haunt him, rising from the Sorgue’s depths: “Now in the form of a nymph or other goddess / from the Sorgue’s clear depths she seems to rise, / and seat herself along the river’s bank.”

VALCLUSA (Vaucluse): The countryside of Vaucluse (from the Provençal for “enclosed valley”) is the site most associated with Petrarch’s verse. Most of his poems are set in an idyllic, woodsy space where the poet wanders alone. Sometimes that space is specifically identified as Vaucluse, as in poem 116, where he describes the welcome isolation of being alone in an “enclosed valley” (valle chiusa in Italian), meditating on a memory of Laura’s face. The green space can either bring peace, as it does in this poem, or provoke pain because of the contrast between the beauty outside and the poet’s pain within. After Laura’s death, the valley is indivisible from his memories of Laura, as in poem 279, in which birds and leaves whisper on a summer breeze, “there where I sit and write, thinking of love.” The gust of wind in this poem is a pun on Laura’s name: “breeze” in Italian is l’aura.

AVIGNON: The most memorable mention of the city of Avignon in Petrarch’s poems has nothing to do with Laura and everything to do with his disgust for the religious schism it represented. Nearly all of Petrarch’s life overlapped with the Avignon papacy (also known as the “Babylonian Captivity”), during which seven successive popes reigned from Avignon, rather than Rome, because of political strife between France and the papacy. Poems 136, 137, and 138 in Petrarch’s collection are known as the “Babylonian sonnets” for their scathing critique of the Avignon popes. In poem 136, he addresses the papal court as malvagia (“wicked thing”) and nidi di tradimenti (“nest of treacheries”), concluding: “you live now such that God smells your stink.”

NASCITA DI LAURA (Birth of Laura): For his 1525 edition of Petrarch’s poetry, Alessandro Vellutello included not only this hand-drawn map but also a series of short introductory essays. In the section outlining his theory about Laura’s identity, he stated his belief that she hailed from the small villages of Cabrières to the northeast of Avignon. Though Petrarch states in his obituary for Laura that he first saw her in the Church of Saint Claire in Avignon, Vellutello theorized that the poems revealed that the two actually met on the walk to church, when Laura stopped to rest under a tree along the Sorgue River.

Both scholar and fan, Vellutello proved to be a massive “shipper” of the two lovers. (A “shipper” is a fan who roots for a relationship.) In 1525, he produced an edition of Petrarch’s poems in which they were completely reordered to create a clear, chronological love story.

Vellutello’s amorous cartography helped inspire the wave of pilgrims who flooded Laura’s tomb when it was supposedly “discovered” in 1533. The cult of Petrarch was sufficiently widespread enough to be satirized: In a 1539 literary dialogue, a Petrarchan fanboy rhapsodizes about traveling to see such “relics” as Laura’s toenail clippers and chamber pot. But mockery could not stymie the fervor. Vellutello’s edition was reprinted dozens of times, embraced by readers enamored of its hybrid nature—at once critical edition and fan fiction.

Printings of Petrarch’s poetry heralded significant changes not only for literature but also for society. Scholars such as Kim F. Hall have highlighted how his praise of Laura’s blond hair and fair skin had an outsized role in making whiteness a Western beauty ideal. However, in other ways, his poems helped usher in an era of women’s literary output in Renaissance Italy. The verse of Vittoria Colonna, the most important woman writer of the Italian Renaissance, was printed in 1538, only a decade after Vellutello’s first edition of Petrarch.

Bay laurel (Laurus nobilis) grows along the fence on the north side of the Herb Garden, near the Banta Terrace of the Rose Garden Tea Room. Photo by Linnea Stephan. | The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Following Vellutello’s footsteps all the way to Avignon might be difficult, but Petrarchan devotees can make a miniature pilgrimage to The Huntington. Your first stop should be to see the laurel growing along the fence on the north side of the Herb Garden. More than a general symbol of poetic fame for Petrarch, the laurel—lauro in Italian—was inextricable from Laura. His quest to possess both is captured in wordplay throughout the poems, as in poem 228, when he describes how Love planted inside his heart a lauro greener than emeralds.

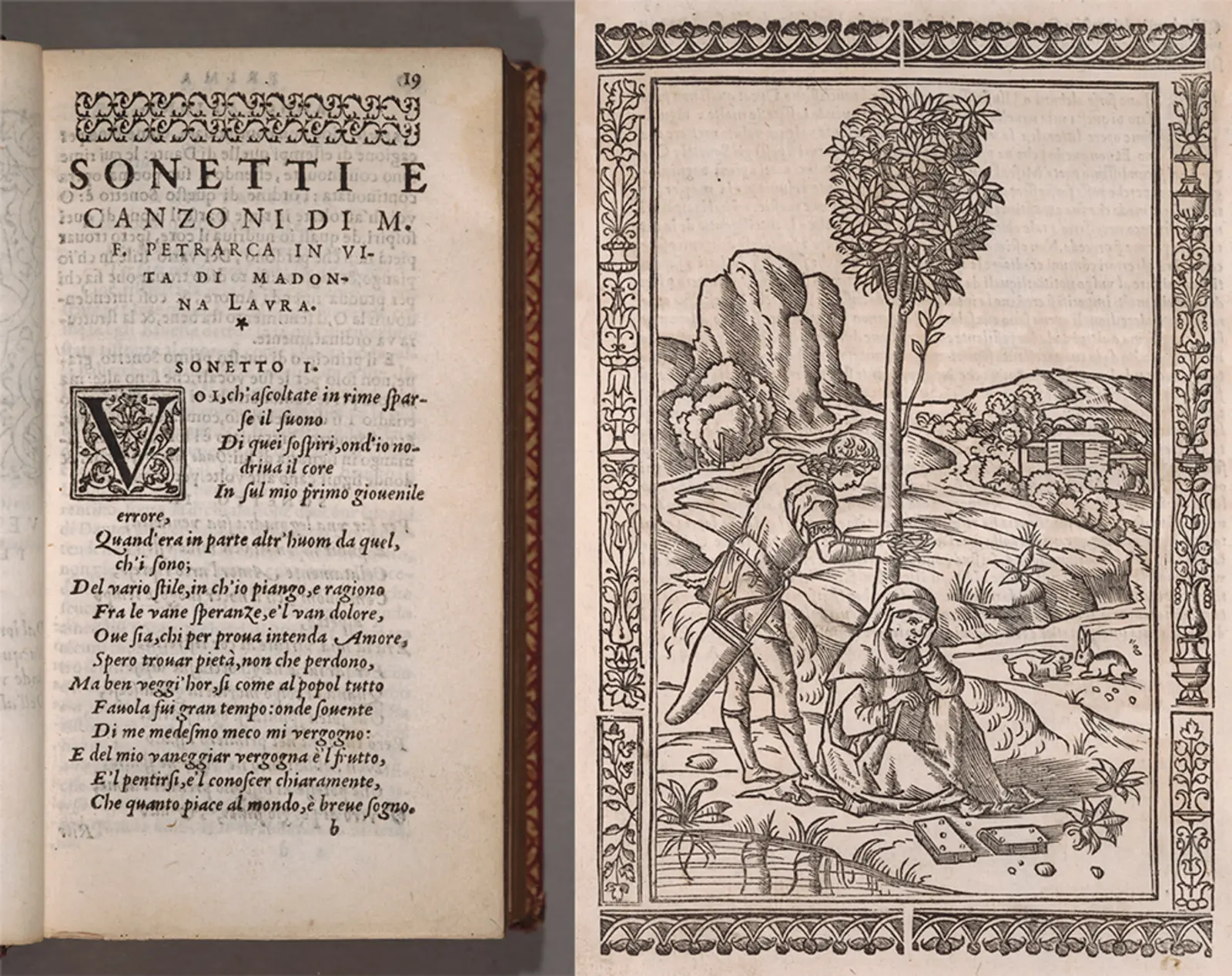

Afterward, visit the Library Exhibition Hall, where one of the treasures currently on display is an early edition of Petrarch’s poetry. His verse is set in a heavy Gothic type, drifting on a sea of erudite exposition. (Because the commentator, Francesco Filelfo, abandoned the project for unknown reasons, this volume contains only the first 136 poems.)

This edition is beautiful and consequential, purchased by Henry E. Huntington himself. But it was created for an audience of elite (and thus, at that time, almost exclusively male) readers. Vellutello’s edition (in The Huntington’s holdings but not on display) may have gotten some facts wrong, but the prominence he gave to Laura’s story proved enticing to a wider audience, including women. Renaissance reactions to this love story anticipated modern fannish reading practices by 500 years—providing strong validation for those of us still “shipping” Petrarch and Laura.

Petrarch’s third and fourth sonnets, with commentary by Francesco Filelfo, early edition of Petrarch’s poetry (RB 104138), 1478, folios 2a3v and 2a4r. Photo by Linnea Stephan. | The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Shannon McHugh, the 2023–24 Molina Fellow in the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences at The Huntington, looks at the book of Petrarch’s poems (RB 104138) currently on view in the Library Exhibition Hall. Photo by Linnea Stephan. | The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Shannon McHugh is an associate professor of French and Italian at the University of Massachusetts Boston and the 2023–24 Molina Fellow in the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences at The Huntington. She is the author of Petrarch and the Making of Gender in Renaissance Italy (Amsterdam University Press, 2023).

You can learn more about Petrarch and Laura—as well as other lovers whose stories can be found in The Huntington’s library, art galleries, and gardens—by signing up for McHugh’s Huntington U class, Love and Death in the Archives.