David Hockney, Tree on Woldgate, 6 March, 2006, oil on canvas, 36 x 48 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of Gregory Evans in memory of Dagny Janss Corcoran. | © David Hockney. Photo credit: Richard Schmidt.

A David Hockney in The Huntington’s venerable European art gallery? Yes, visitors can view the large and striking Tree on Woldgate, 6 March (2006), which depicts the serene Yorkshire countryside where the renowned artist grew up. You can see fields in the distance and, in the center, a leafless tree with branches that twist and turn in an almost snakelike manner. The painting comes from a period in Hockney’s career when he created a series of plein air landscapes around his hometown.

The painting hangs in conversation with John Constable’s monumental View on the Stour Near Dedham (1822). While the two works were created more than 180 years apart, their inspiration comes from the same source—childhood surroundings—and they both convey a sense of place and nostalgia.

One of the most famous British artists of the 20th century, Hockney emerged as a major contributor to the 1960s pop art movement and has had a multifaced career as a painter, draftsman, printmaker, stage designer, and photographer. He is perhaps best known for his acrylic paintings of bright swimming pools, split-level homes, and suburban California landscapes.

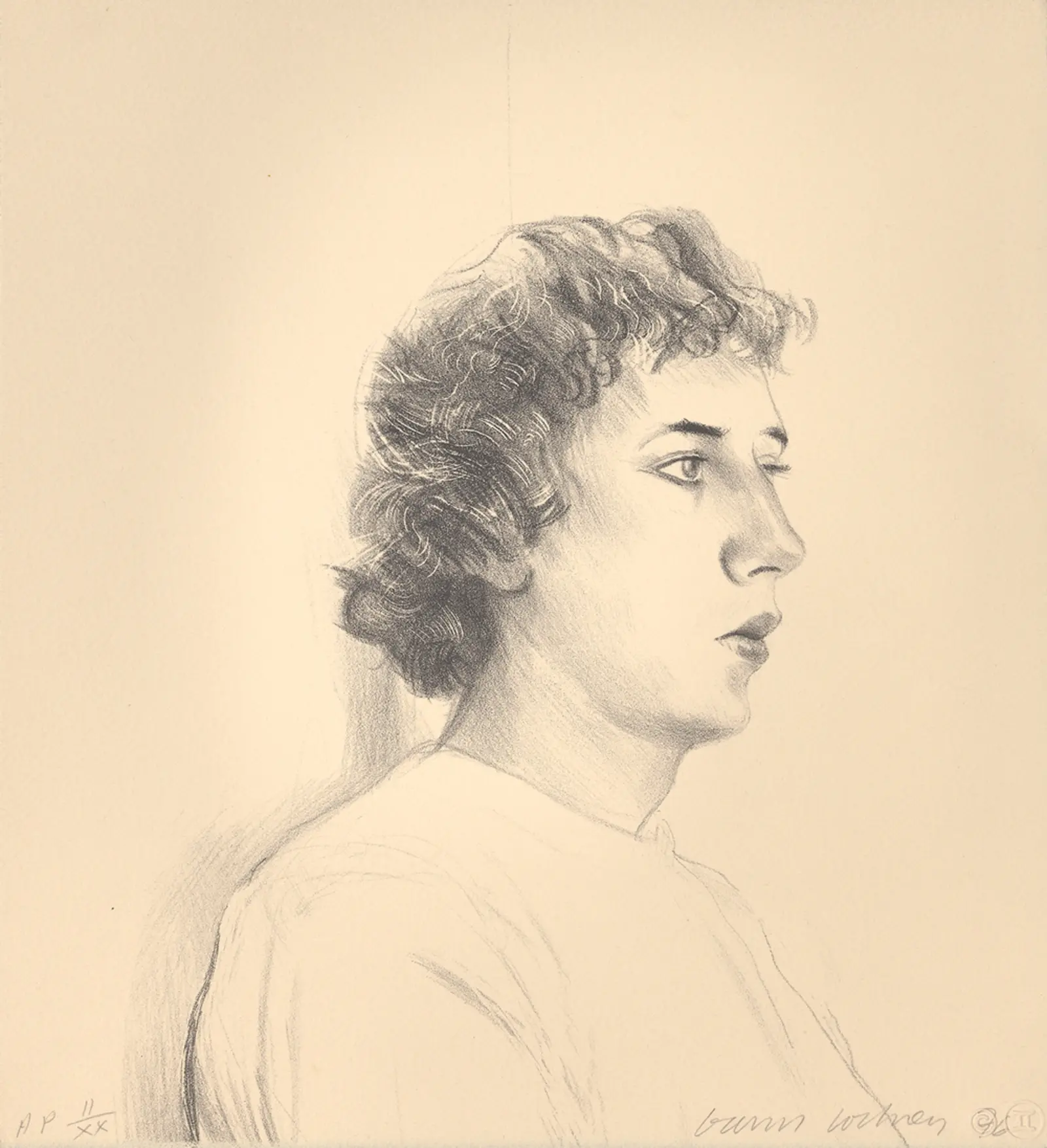

David Hockney, Self-Portrait with Red Braces, 2003, watercolor on paper, 24 x 18 1/8 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of Gregory Evans in memory of Nicholas Wilder. | © David Hockney. Photo credit: Richard Schmidt.

In 2022, The Huntington acquired its first Hockney works: 17 works on paper that include an artist book, drawings, prints, photocollages, and watercolors. These works display an intimate side of Hockney—like the self-portrait of the artist in red suspenders, bent over a table and peering over his wire-rimmed glasses, paintbrush in hand. His blue eyes, gazing straight at the viewer, create an immediate intimacy.

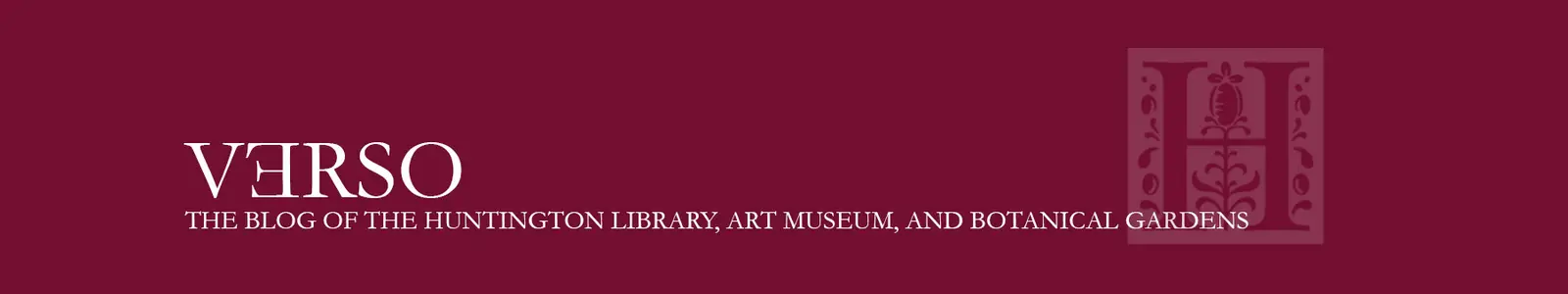

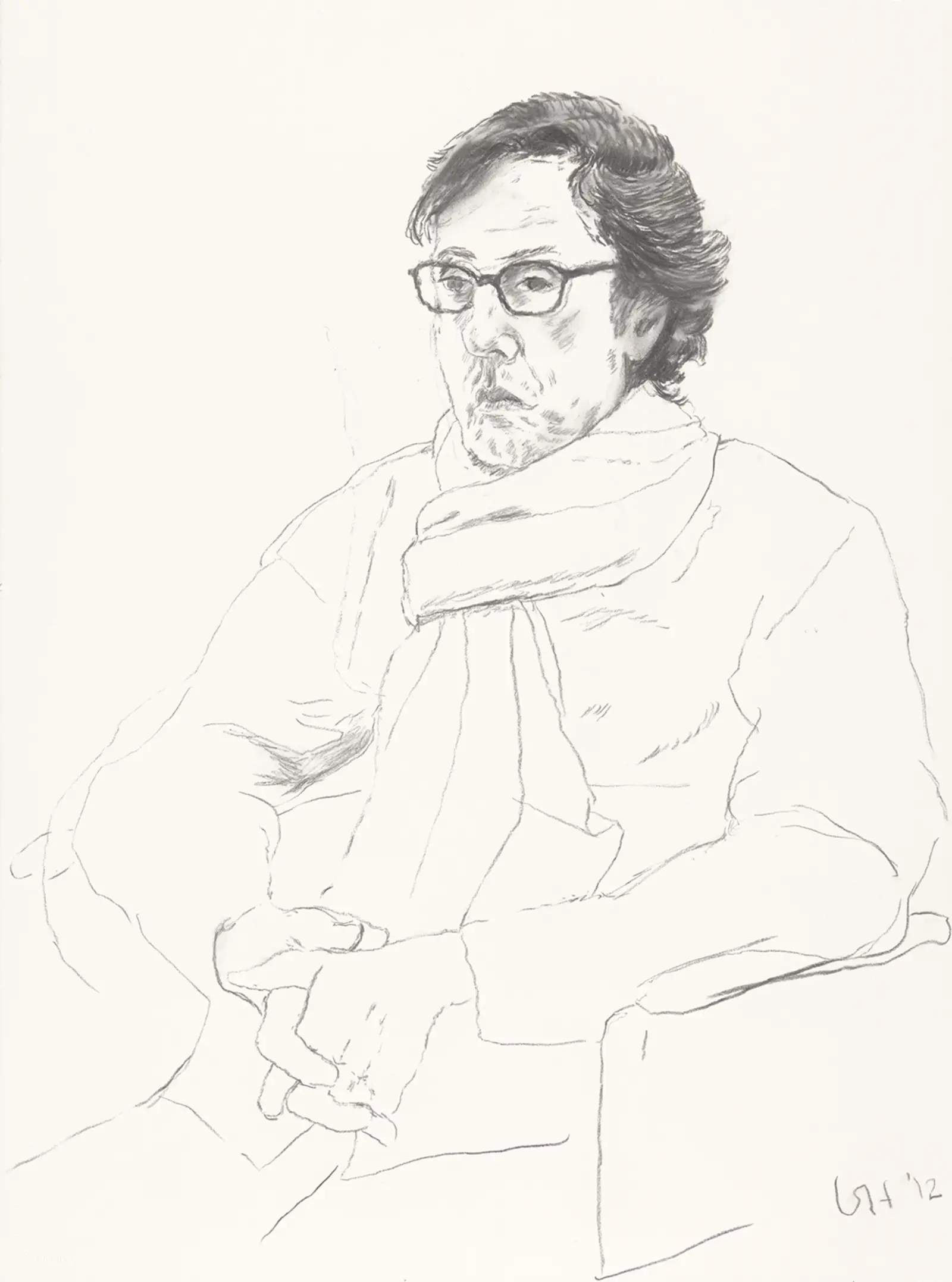

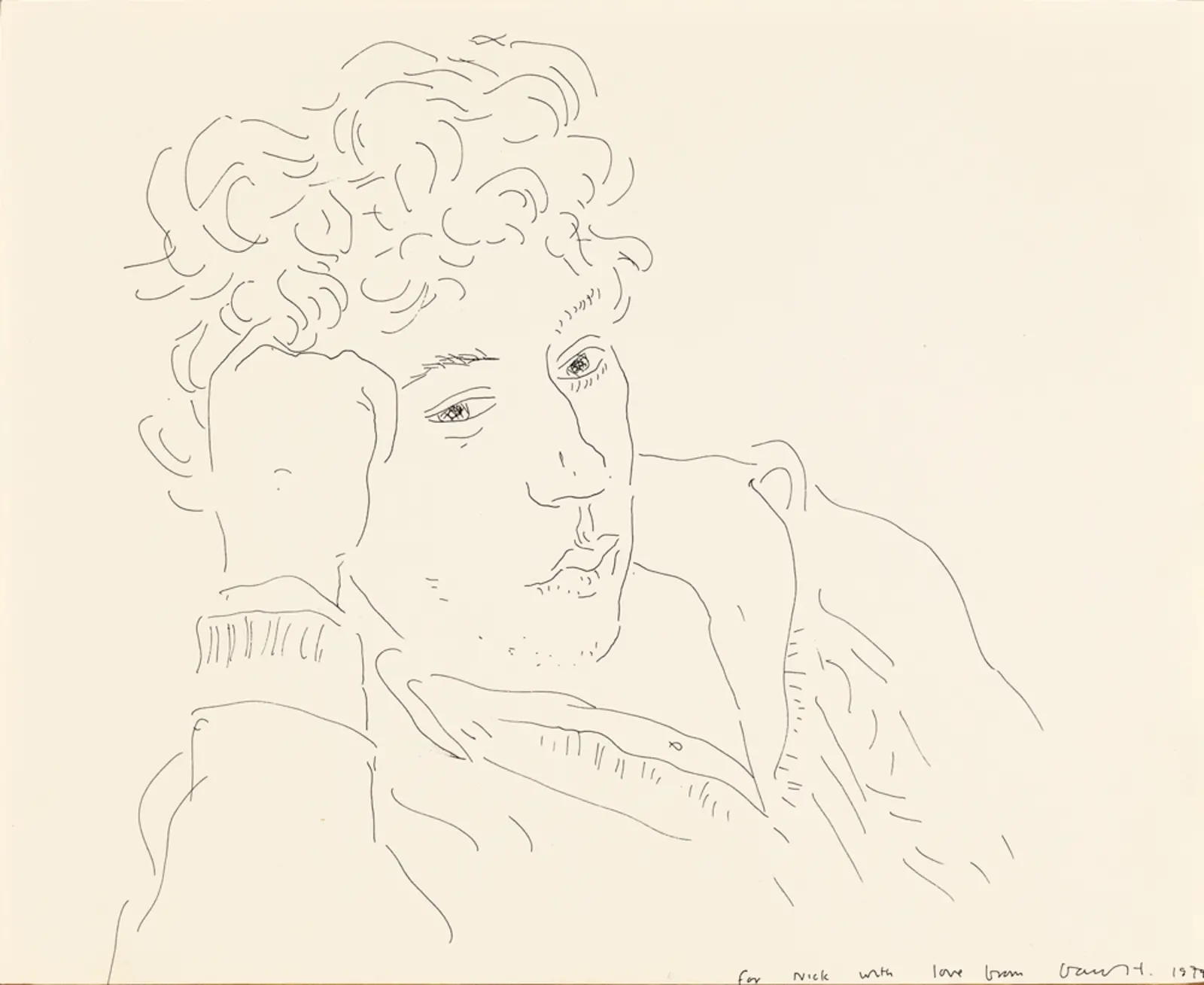

Most personal of all are the ink-on-paper portraits of Gregory Evans, who had a close romantic and business relationship with Hockney for many years.

How did The Huntington become the stewards of these prized depictions? Evans first visited The Huntington in the 1970s and, over the years, has enjoyed the serenity of the grounds and the freedom to explore—from the Desert Garden’s cacti and the Japanese Garden’s bamboo grove to the art galleries. “The Huntington has always been a sanctuary for me,” Evans said.

Evans’ more recent involvement with the Isherwood Foundation led him to attend the Isherwood-Bachardy lectures at The Huntington, which holds the papers of the British novelist Christopher Isherwood and works by artist Don Bachardy—both close friends of Hockney and Evans.

While spending time again at The Huntington, Evans thought to himself that this was the place where he wanted to donate his artworks by Hockney. “It just felt right,” he said.

Hockney and Evans met in the 1970s. Evans soon became the model and muse for many of Hockney’s works and eventually served as Hockney’s curator and business manager. The gifts to The Huntington document Evans and Hockney’s romantic relationship and capture its tenderness.

David Hockney, Gregory, 1979, ink on paper, 14 x 17 in. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Gift of Gregory Evans in memory of Nicholas Wilder. | © David Hockney. Photo credit: Richard Schmidt.

In David Hockney: Drawing from Life, a book that accompanied a 2020 exhibition of the same name at the National Portrait Gallery in London, Hockney stated that “what an artist is trying to do for people is bring them closer to something, because of course art is about sharing; you wouldn’t be an artist unless you wanted to share an experience, a thought. I am constantly preoccupied with how to remove distance so that we can all come closer together, so that we can all begin to sense we are the same, we are one.” Through the once-private artworks donated by Evans, viewers will be drawn closer to Hockney’s distinctive way of observing the world around him.

Evans donated the works to The Huntington under one condition: They will be available to lend to other institutions. Six of the works on paper will have their first excursion this year, traveling to the National Portrait Gallery in London to take part in the exhibition “David Hockney: Drawing from Life,” the 2020 show that closed after only 20 days because of the pandemic. The museum will reprise the exhibition this fall.

Keisha Raines is the communications associate in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington.